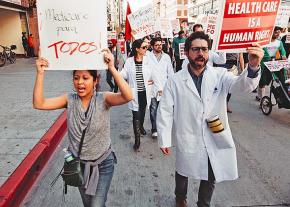

How can we win Medicare for all?

, a registered nurse in New York City and member of the board of directors of the New York State Nurses Association, considers what it will take to win a real national health care system, in an article first published at Jacobin.

THE RECENT debates about Medicare for All in the United States reflects a number of positive developments. For one, the campaign for truly universal health carehas gained serious momentum for the first time since the Affordable Care Act (ACA) passed in 2012. At that time, despite valiant efforts to insert a single-payer proposal, most politicians and activists stayed loyal to President Obama's public-private partnership strategy.

Before the ACA, Michael Moore's 2007 documentary Sicko--which focused on the victims of the for-profit health insurance industry rather than on the United States' exclusion of fifty million people from health care coverage--provided a serious boost to activist organizing for Medicare for All.

The only other time in the last forty years that Medicare for All took center stage was in 1992, after Bill Clinton made universal health care a frontline campaign promise. Hillary Clinton's subsequent task force buried that possibility after handing out shovels to the health insurance industry.

It therefore seems fitting that her historic failure of a presidential campaign has paved the way for this much-needed resurgence in the movement for universal health care. A coalition of single-payer activists groups--including National Nurses United (NNU), New York State Nurses Association (NYSNA, of which I am a member), Amalgamated Transit Union, United Electrical Workers, and a number of smaller unions and locals grouped together as the Labor Campaign For Single Payer Healthcare, Physicians for a National Health Program, and Healthcare-NOW--are stepping up the fight for health justice.

In January, this network of Medicare-for-All supporting organizations settled on a new strategy. Instead of reacting to Trump, the groups decided to go on the offensive. We agreed that, while the ACA lacks public support and perpetuates an unequal system, Trump's health care proposals will be much worse. In this context, Medicare for All will gain popularity on the local, state, and national level. The guiding idea--validated by Bernie Sanders's campaign and Hillary Clinton's defeat--was that you can't fight the Right from center.

Changing the Political Landscape

The Medicare-for-All movement is engaged in a number of strategic debates right now. Should we puruse a state-based legislative strategy or a national one? How much of our collective resources should we devote to political lobbying and electoral campaigns versus broader political organizing? How do we organize the millions of health care victims? How do we build Medicare-for-All committees in communities and workplaces?

But the question receiving the most attention, especially among the growing socialist movement, is whether we should hold a national march. Jacobin has published multiple arguments on either side of the debate, and the authors have brought important considerations to light.

I'd like to offer my perspective as an organized socialist, a pediatric emergency room nurse in a public hospital who has built several successful (and many failed) workplace campaigns, an active participant in the Medicare-for-All movement, and an elected leader of the NYSNA. I believe that a national march can push us further toward our goal, but only if a coalition of unions, socialist organizations, and other social forces combine efforts to build a large, unified mobilization.

First off, our movements need to build power to win. Their side has money, our side has collective action. All progressive movements must figure out how to use this power in the face of obstacles.

A national march would play a positive role in this process. We shouldn't overstate the effects of Washington, DC, days of action. Some produce little discernable change, and not all are worth the time and energy required to plan them. But they can transform the people who participate in them, advancing a number of critical ideological and organizational processes.

Even some supporters of the national march proposal dismiss its effects on the political landscape. But a cursory glance at similar mobilizations from the last twenty years should convince them otherwise. The anti-globalization actions from 1999 through 2001 in Seattle, DC, and Los Angeles helped develop a critical approach to institutions like the WTO, IMF, and World Bank, as well as policies like North American Free Trade Act (NAFTA) and the Free Trade Area of the Americas. They created a generation of activists who built power throughout the 2000s, culminating in Occupy Wall Street. Those who participated in the Battle for Seattle likely didn't know that their work would set the stage for the activists in Zuccotti Park, but we can't tell the story of the Occupy movement without reference to these earlier struggles.

Likewise, the global day of action on February 15, 2003, drew over one million protesters to New York City to resist the Iraq war. The New York Times called the new antiwar movement the world's second superpower.

This year, the Women's March helped set the tone for resistance to Trump's agenda, erasing any belief that the new president had a popular mandate.

Michael Kinnucan, in his argument against the national march, sees these events differently. He writes, "While some [marches] have shaped the national mood, none has significantly altered the political landscape."

Perhaps this statement depends on how you define "political landscape." A more narrow view would only rate actions as successful if they move politicians to change their public positions. Indeed, Kinnucan offers only dismal predictions for a Medicare march:

It is hard to imagine how demobilizing and dispiriting this project will be for the activists involved, many of whom are new to politics ...

A futile march on Washington will not interest anyone except the tiny minority of Americans who already support single payer, who already engage in left-wing activism, and who can travel across the country for a protest.

But many protesters I've marched with take different lessons from these mobilizations. Time and time again, I come away from national demonstrations with the conviction that even the most routine event can change thousands of people's lives forever. Indeed, my experience reminds me of a John Berger quote, which appeared in this excellent article about the Women's March:

The importance of the numbers involved is to be found in the direct experience of those taking part in or sympathetically witnessing the demonstration. For them the numbers cease to be numbers and become the evidence of their senses, the conclusions of their imagination. The larger the demonstration, the more powerful and immediate (visible, audible, tangible) a metaphor it becomes for their total collective strength.

When we consider the health care march, we should expand our understanding of the political landscape to include how an action changes popular opinion, provides momentum for the movement, and politically develops the participants. From that perspective, the strategic question becomes not whether a national march is ever useful, but whether the outcome in a particular moment justifies the effort that went into it.

So far, this strategy has been vindicated. In the face of various iterations of Trumpcare, angry voters confronted their representatives at fiery town hall meetings. Medicare-for-All initiatives in California and New York came within one or two votes of reaching their governors' desks. As is often the case, overt and covert Democratic Party obstruction killed these bills, but the legislation garnered more support--both from politicians and voters--than ever before. Indeed, a recent poll shows that 62 percent of Americans now believe that the government should make sure that everyone has health care coverage.

This means that while Trump, McConnell, and Ryan are trying dismantle as much of the federal government's responsibility for health care coverage as they can, almost two-thirds of the population wants the exact opposite. And many of them know that the status quo of Obamacare is not going to get us there.

Yes, We Should March

For the first time since Medicaid and Medicare came into being, we are within striking distance of a successful fight for universal health care. But we are not yet on the precipice of victory. We desperately need to develop the social forces capable of challenging both parties' pro-corporate obstinance toward government-provided health care.

Again, Guastella makes an important intervention. He states that we can count on some support from Democratic congresspeople, but we shouldn't depend on that to win. The political establishment, whether Republican or Democratic, will reflect the balance of class forces. We must force the issue, which means we must develop a national movement.

We should therefore be wary of politicians who want to direct our energy toward electoral campaigns. The diversion of antiwar forces toward John "reporting for duty" Kerry's presidential campaign in 2004 is just one infamous recent example.

Barney Frank's pithy dig at the National Equality March in 2009 follows the same logic: "The only thing they're going to be putting pressure on is the grass." He was wrong. That protest helped provide the momentum for the social forces that won marriage equality fights across the US.

Fortunately, this perspective has not appeared in the current debate in Jacobin, but we should expect it to enter the conversation soon. The Democratic Party has co-opted many social movements, lowering supporters' expectations and wasting their time and energy. The Medicare-for-All movement is not immune to this danger.

It is the right time to push for Medicare for All. We have state-based momentum, and these campaigns aren't likely to heat up again until spring of next year. Meanwhile, activists will be fighting the various sequels to the Trumpcare debacle for the next several months. Perhaps most importantly, Senator Bernie Sanders is set to release his national single-payer bill. The Medicare-for-All movement needs a goal that will help broaden its base and inspire the next big push. A national march can do just that.

First published at Jacobin.