An unflinching commitment to democracy

pays tribute to a socialist scholar and an activist for half a century.

I MET Bill Pelz, who passed away in 2017, for the first time in the fall of 2008. He graciously accepted an invitation to deliver a paper at a conference that a German colleague and I had organized at State University of New York-Potsdam, a small liberal arts college in upstate New York.

Bill, being very much the urbane Chicagoan, seemed amusingly out of place in our rural college town. When I recommended a hiking and camping trip into the nearby Adirondack Mountains later on, Bill could only express his bewilderment at why anybody would voluntarily sleep in a tent instead of opting for the comforts of a hotel. To him, spending a night under an open sky was something forced upon our distant ancestors by necessity, not a fate freely chosen by any rational person.

What Bill lacked in camping skills he more than made up with his legendary good humor and gift for friendship. He was a bon vivant, who truly delighted in fine dining and a multitude of brewed beverages. I vividly recall receiving several Christmas cards from him, with the unifying declaration: "Marx: Right about Capitalism. Right about Beer."

To me, Bill's indefatigable personality has often evoked the milieu of Marx and Engels in London, as it was so colorfully described by Wilhelm Liebknecht in the latter's famous Karl Marx: Biographical Memoirs of 1896. Bill, of course, had a life-long interest in Wilhelm Liebknecht and edited one of the best anthologies of Liebknecht's writings in English. The circle of friends and comrades that coalesced around Marx and Engels, between the 1850s and the 1870s, was famously characterized, and in equal measure, by intense political and philosophical debates as well as frequent visits to pubs.

Bill's political and intellectual trajectory had been shaped by the hope that humanity can do better than capitalism. His vision of a socialist alternative remained rooted in his commitment to substantive equality, truly universal human rights, and participatory democracy from below.

Bill agreed wholeheartedly with Marx's famous admonition that understanding and analyzing the world must go hand in hand with political activism, in order to change it. Hence, Bill could never confine himself to being an armchair scholar or a mere Marxist academic, aloof from direct involvement with the struggles of his time. Instead, he saw his role as a Marxist in academia as a challenge to combine scholarship with activism and political organizing.

Over the decades, Bill became an increasingly prominent figure on the left in Chicago and beyond, being deeply involved with a variety of groups, organizations, and institutions there. Starting with Students for a Democratic Society (the main organization of the New Left during the 1960s), which he joined shortly before its demise, Bill became active in the Chicago branch of the International Socialists in the early 1970s and eventually helped build and run two radical bookstores, which functioned also as local organizing and political information centers: the Red Rose Collective as well as the New World Resource Center.

His political trajectory led him to socialist organizations, such as Solidarity, the Socialist Party USA (where he served as International Secretary), and the Democratic Socialists of America, where he directed their Chicago Political Education Office. He was also, and increasingly so, an ally to the International Socialist Organization.

BILL PELZ proudly identified with his own working-class origins even when he became an increasingly well-known historian and activist.

His diverse scholarly oeuvre focuses on the plight of working people on both sides of the Atlantic and their efforts to not only resist exploitation and subjugation, but also fight for a better world. Fighting for such a better world requires, as Bill often emphasized, not only a vision to strive for, but also a systematic analysis of the history of past struggles, with an eye for attempting to learn from both their successes and their failures.

In 1988, Bill's Ph.D. dissertation The Spartakusbund and the German Working Class Movement, 1914-1919, was published by Edwin Mellen Press. This volume was followed by Wilhelm Liebknecht and Social Democracy: A Documentary History, originally published by Greenwood Press in 1994. Haymarket Books of Chicago republished a revised version of this volume in 2016.

In 2000, Bill put together his Eugene V. Debs Reader, printed by the Institute for Working Class History in Chicago. Just like his collection on Wilhelm Liebknecht, the Eugene V. Debs Reader has been re-issued recently, when Merlin Press in London published a revised edition in 2014.

In 2007, Bill's Against Capitalism: The European Left on the March came out, chronicling the history of the European labor movement during the late 19th and early 20th centuries in an accessible fashion. Yet, while this book focuses on key developments in Europe, such as the Paris Commune, the rise and fall of the First and Second Internationals, as well as the Russian Revolutions of 1917, Bill remained keenly aware of the global reach of capitalism by balancing his narrative with references to developments outside of Europe, such as the Boer Wars in South Africa as well as various anti-colonial movements.

This volume, conceptualized as an introductory text for college students and a general readership, was succeeded by Karl Marx: A World to Win, (Pearson Longman Publishers, 2012). This concise volume introduces the thinking and personality of Marx, with Bill's signature wit.

Bill's love for cats was truly Leninist. Some, like his beloved Engels and Sputnik, were explicitly thanked in the introduction of his books, for their patience and overall support during the writing process. Bill could not resist subverting the customary acknowledgment blurb, noting that any mistake and/or error in the text's judgment was, of course, not the fault of anyone else but...his cats, who alone should be blamed and scorned accordingly.

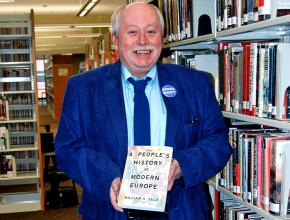

Last but not least, there is Bill's A People's History of Modern Europe, published by Pluto Press in 2016. In sixteen chapters, he describes and analyzes the history of Europe since the Middles Ages--through the history of ordinary people--thus departing from the standard perspective of the political, socio-economic, and cultural elites that still dominate most popular and academic historical surveys.

Bill examines not only the oft-barbaric levels of exploitation of working people, by the various ruling classes, but also emphasizes resistance and class struggle, ranging from the Peasant Wars of the 1520s all the way to the struggles for universal voting rights and gender equality in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Sadly, Bill will not see the publication of his last book: A People's History of the German Revolution, scheduled to come out in the late spring of 2018. Much like his A People's History of Modern Europe, this volume is inspired by Howard Zinn's famous A People's History of the United States.

Zinn wrote the introduction to the first edition of Bill's anthology of the writings of Eugene Debs and had an impact on his political and scholarly development. Like Zinn, Bill rejected the pretense of intellectual neutrality and instead openly identified with the perspective of the downtrodden, the oppressed, the exploited and the marginalized. He understood that revolutions should be approached not only in terms of what they failed to archive but also in terms of what could have been.

A successful German revolution in 1918-1919 would have opened up other historical possibilities, rather than the trajectory that led to both Stalin and Hitler, among other developments. The historian's craft, if done well, should convey a sense of the ultimate "openness" of historical developments to a range of different possible outcomes.

IN ADDITION to his various publications, the Institute for Working Class History was a labor of love for Bill, who created it as a non-profit in 2000. The Institute's website describes its mission thus: "The Institute of Working Class History is an independent, non-partisan educational organization dedicated to the examination and promotion of the history of the common people." By the time of Bill's death, the IWCH was in the process of developing a joint book series with Pluto Press.

Bill dedicated much of his time to the exploration, analysis, and promotion of the life and thought of Rosa Luxemburg. Having been involved with the International Rosa Luxemburg Society for many decades, he participated in and organized conferences and workshops in North America, Europe and Asia.

In addition, Bill was also an active member of the editorial board of the English edition of the Collective Works of Rosa Luxemburg and, together with Peter Hudis and myself, edited volume three. That volume, which focuses mainly on Luxemburg's journalistic pieces during the Revolution of 1905, is slated to come out at the end of 2018 by Verso Books.

Bill Pelz was drawn to Rosa Luxemburg for her unflinching commitment to socialism and democracy that were intrinsically linked. There cannot be any meaningful socialism without democracy, as the sad examples of the so-called "real-existing" socialism in the Soviet Union and her satellite states amply illustrated.

Thus, there cannot also be any kind of meaningful and lasting democracy, going beyond empty electoral ritualism, without political democracy being augmented by economic democracy, which is the essence of socialism. One does not have to be a Marxist to understand this trajectory, as Thomas Piketty and the so-called Princeton Study demonstrate.

To Bill Pelz, the socialist vision was not a call for any one-party dictatorships or a mere return to Keynesian welfare state capitalism, but the expansion of civil society, substantive equality, and the withering away of any oppressive state apparatus.

Bill's kindness, his warmth, his humor, his humanity, as well as his determination to fight against injustice and for a better world, are at least in part preserved in his books. May they continue to sustain and inspire us as we carry on our struggle.