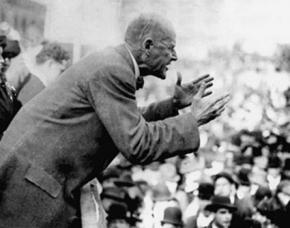

Introducing...Eugene Debs

, a socialist and former railroad switchman, reviews a new documentary about the early 20th century socialist leader Eugene V. Debs.

RECENT POLLS show that over 55 percent of Americans under the age of 30 now have a favorable view of socialism. Many of these young recruits to the vision of a better world are ready to learn about what's now become their own history.

Malcolm X stressed "learning something about the past, so that we can better understand the present, analyze it, and then do something about it." There is no better place to begin this process than by learning the story of Eugene Debs.

The new documentary American Socialist: The Life and Times of Eugene Victor Debs is a labor of love for filmmaker Yale Strom. Trying to contain more than half a century of activism in a 93-minute format is an impossible challenge, but Strom manages to capture the essence of Debs--and that's a good start.

The two passions that Debs took to his grave were industrial unionism and socialism. To understand how Debs came to see the need for industrial unions, the story of the Railroad Brotherhoods is essential. Here the film is lacking, so I'll outline it here

In the years before the formation of the American Railway Union, there were a half-dozen competing craft unions in the operating department alone. Firemen, engineers, brakemen conductors, switchmen and trainmen each had their own organization. The railroad bosses skillfully played one craft against another and kept labor on the defensive. It was time to build an industrial union for railroad workers.

In June 1893, with Debs in the lead, the American Railway Union (ARU) was formed. Its growth was meteoric--in the short time between its founding and the Pullman strike, over 460 locals were formed.

American Socialist does a good job of capturing the breadth and fury of the 1894 Pullman strike, using photographs and narration to condense a complex story into several minutes.

"STRIKE IS NOW WAR" screamed the Chicago Tribune headlines, and for the 30 strikers who were killed in the strike, it was a battle to the death. Debs moved to Chicago to take a leadership role in the strike.

Debs had voted for Democratic presidential candidate Grover Cleveland three times, and now he saw hundreds of federal troops massing outside his Michigan Avenue hotel room, mobilized by the same President Cleveland. They were there to break the strike.

After being sent to jail in Woodstock, Illinois, for his role in the Pullman strike, Debs came to two conclusions after the Pullman Strike: no more Democratic Party and no more capitalism.

The defeat of the Pullman strike and the ARU had a lasting impact on railroad unionism. To this day, American railroads are hamstrung by an assortment of craft unions, often in competition with one another for members and job assignments. At the same time, the heroic ARU served as a template for the surge of industrial unionism with the rise of the CEO in the 1930s.

WITH THE formation of the Socialist Party (SP) in 1901, Debs' focus shifted to a tireless fight for socialism. Debs ran as a Socialist Party candidate for president five times, and in between the campaigns, he was a tireless organizer and journalist and co-editor for the Appeal to Reason.

In 1908, he crisscrossed the country on a train known as the Red Special, setting a new standard for presidential campaigns in the 20th century.

The long and bitter struggle between the SP's reform and reformist wings is hardly mentioned in the film. Debs, firmly in the revolutionary camp of the party, disliked internal conflict.

This non-sectarian attitude was partly a strength and partly a weakness in Debs' makeup. Abstaining from fights inside the SP often resulted in the more conservative "sewer socialist" wing having its way.

Director Yale Strom takes an interesting sidebar in exploring grassroots socialism in the heartland states of Oklahoma, Texas and Kansas. The relationship to Debs' biography is that Debs spent a lot of time working on the Appeal to Reason, which was based out of Kansas. But this segment generally captures the spirit of rural socialism.

Finally, the movie examines the most principled fight in a life full of principled fights: opposition to the imperialist First World War. Whether to support or oppose the war was a test for socialists worldwide, and Debs passed this test with a speech in Canton Ohio.

Knowing the speech would put him in jeopardy of violating the newly minted Sedition Act of 1918, Debs gave it anyway. Already in his late sixties and in poor health, Debs ended up spending two and a half years in a federal prison.

American Socialist contains rare footage of Debs' release from prison. His fellow inmates rose as one to salute their comrade who once wrote, "While there is a soul in prison, I am not free."

The movie would have benefited from having a blue-collar worker or an active labor leader as a commentator to help round out this tribute to a fire-breathing revolutionary who went to work at the age of 15. See the movie, bring a friend, have a beer afterward--and, by all means, talk socialism.