Where is Syria’s revolution going?

examines the latest phase of Syria's revolution, the politics of the opposition and the U.S.-led sanctions campaign against the Assad regime.

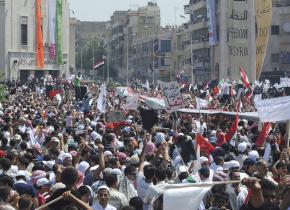

AFTER NEARLY six months of continuous mobilization in the face of savage repression, the Syrian revolutionary movement is debating its future as the U.S. tries to manipulate the opposition to suit its own aims in the Middle East.

The struggle in Syria continued after Friday prayers on August 26--called the day of "patience and determination" by protesters. According to the Local Coordination Committees (LCC) of Syria, the grassroots revolutionary network, 11 people were killed that day, which saw tanks surround 2,000 people to prevent a protest outside a mosque in a Damascus suburb.

The repression came after the regime of Bashar al-Assad intensified the crackdown in several cities--which according to some witnesses included an attack on the port city of Latakia by naval boats on August 14. According to human rights organizations, some 2,500 people have been killed since the protests began in March. Uncounted thousands have been arrested--many of them tortured.

Yet there was little sign that this latest killing of unarmed protesters would quell the revolt. On the contrary, the regime's ability to carry out repression is limited by the number of reliable troops, estimated by revolutionary activists at about 50,000 soldiers.

As a result, when elite military units have used tanks and artillery to carry out serial assaults in rebellious cities, including Homs, Daara, Hama, Latakia and Jisr al-Shughour, protests in much of the rest of the country continue with much less repression. The bulk of the armed forces, comprised mainly of Sunni Muslim conscripts, are apparently deemed unreliable for carrying out such attacks.

With the military only partly reliable, the government has counted on multiple security services and paid thugs, known as shabiha, to play a key role in the crackdown. But neither have they succeeded in stopping the mass demonstrations.

The result has been an impasse in the revolution. The mass movement keeps taking to the streets--unarmed, and with the full knowledge that dozens might be killed on any given day, and still more arrested and tortured.

But everyone in the movement knows that if the mobilization falters, a reign of terror would follow that would lead to the butchering of tens of thousands. That's exactly what happened in 1982, when the Syrian government of Bashar al-Assad's father, Hafez al-Assad, ordered the military to slaughter an estimated 10,000 people in the city of Hama to wipe out a Sunni Muslim insurgency.

SO THE mass protests continue, with the aim of winning over the final bastions of support for the regime among people in the religious minorities traditionally sympathetic to it.

Historically, the Syrian regime's base includes Christians, Druze and, most importantly, members of the Alawite Muslim sect, about 12 percent of the population. Alawites hold key positions in the state bureaucracy, the armed forces and in the security services.

A number of Alawites--historically a poor, persecuted and mostly peasant population--were attracted to military careers as a means of social advancement and gravitated to the secular Baath Party that took power in 1963. The Alawites rose to greater prominence after Hafez al-Assad came became president in 1970.

The Baathist Party regime--which has been led by the two Assads, father and son, since 1970--has survived many challenges in the past, from war with Israel to constant imperialist pressure led by the U.S.

Syria recovered from its military defeats at the hands of Israel by intervening in Lebanon's civil war in the 1970s. This provided the Syrian regime with economic breathing space and political leverage in the Middle East, via the forces that became Hezbollah in Lebanon, and ties to key factions of the Palestinian movement. The U.S. even blessed Syria's dominance of Lebanon in 1991 in exchange for Syria's support for the 1991 Gulf War against Iraq.

But the Syrian regime has also felt rising pressure in recent years, both from the U.S. and Israel, and from the contradictions of its economic policies.

The collapse of Syria's long-term ally, the USSR, in 1991 was an economic and political blow. A decade later, the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq was intended to be a step toward ousting Syria's regime, among others. Assad responded by allowing Sunni Islamist fighters to cross into Iraq and keep the U.S. military tied down.

Despite the U.S. military's difficulties in occupying Iraq, Syria was nevertheless now sandwiched between Israel and the world's most powerful military. Then, in 2005, mass pressure in Lebanon forced the Syrian military's sudden withdrawal from that country. This was not only a major political setback, but an economic blow as well--some 1 million Syrians were working in Lebanon at that point.

To adapt to this political and economic blow, Syria accelerated "market reforms"--that is, opening up the economy to private capitalists who increasingly encroached on the state-owned industries and political patronage networks that had dominated the Syrian economy under the Baath Party rule. Inequality grew as well.

Peter Harling and Robert Malley of the pro-imperialist think tank, the International Crisis Group, correctly point out that these economic changes helped set the stage for the revolution:

For the most part, the regime has been waging war against its original social constituency. When Hafez al-Assad, Bashar's father, came to power, his regime, dominated by members of the Alawite branch of Islam, embodied the neglected countryside, its peasants and exploited underclass. Today's ruling elite has forgotten its roots. Its members inherited power rather than fought for it, grew up in Damascus, mimicked the ways of the urban upper class with which they mingled, and led a process of economic liberalization at the provinces' expense.

The regime's turn should have opened the way for genuine socialist and working-class politics, quite different from the rhetoric sometimes used by the regime. However, the Syrian Communist Party long ago become an adjunct of the Baathist regime and is completely discredited. Thus, what are essentially class questions are often channeled along sectarian and tribal lines.

No longer able to offer the prospect of improved living standards to the impoverished majority, the Assad regime is trying to retain its hold power by pumping up fears of sectarian strife.

The government claims that "armed gangs" and Sunni Muslims--who make up the majority of the population--would impose an Islamist fundamentalist state on religious minorities. At the same time, Bashar al-Assad and his circle apparently hope that by carrying out increasingly intensive crackdowns in targeted cities, they will intimidate the opposition across the country. So far, they haven't succeeded.

IF THE regime hasn't been able to destroy the movement, the revolutionary forces are themselves divided about what strategies and tactics to use to drive Assad from power--and whether to accept support from imperial powers.

Some of the more conservative elements in the opposition have pointed to the overthrow of Muammar el-Qaddafi in Libya as evidence that backing from the U.S. and NATO should be welcomed. Indeed, the Libya developments are sparking intense debates, as Joshua Landis explains on his Syria Comment blog:

The Facebook [Syrian] Revolution Page reveals the "Libya effect" on the Syrian opposition. The admin keeps pushing the "selmiye" or "peaceful" message. Commentators are largely getting upset and claiming that the Syrian revolution is losing momentum. Many claim that peaceful methods are flagging and cannot win against Syria's determined and far superior security forces. They want a real military struggle like Libya's.

Others on the Arab left sharply disagree. According to Talal Salman, editor of As-Safir, a leftist Lebanese newspaper:

The return of colonial powers dressed as liberators is more dangerous than anyone can imagine. "What a miserable choice it is that the dictators impose on the people of the Arab world: Either they lose their voice and give up their rights in their countries and agree to live without dignity, or they live under colonialism that comes this time under new slogans of liberation, ending oppression and giving the land back to its people.

In the meantime, attempts are being made inside and outside Syria to give shape and organizational form to the movement.

A group of opposition figures met in Turkey in August, but the results of their effort are unclear. Syrian dissident Obeida al-Nahhas told the Associated Press that a council had been formed, but others disagreed.

Other sources told the newspaper Asharq Alawsat that the National Council "will be made up of between 115 and 125 members" and that "coordination is taking place with the Syrian opposition inside Syria to ensure that the 'National Council' represents the Syrian people, of all different backgrounds and sectarian affiliation."

Some in the opposition, however, are against national councils created outside Syria. As Damascus Media and Communication director Ashraf Miqdad said to the daily website Elaph:

They are spending millions on imaginary conferences, when they should be supporting the Syrian people inside Syria. They should postpone declaring any council until there is a unified decision. We want people with a history who actually represent the inside...They are looking at the Libyan experience and they want to implement it in Syria, but the difference is great.

Also speaking to Elaph, Syrian dissident Abu Dhad Salem Al Salem asked:

How can a council be created out of failed conferences which have only provided the revolution with further divisions?...The Syrian opposition forces abroad are racing to form councils, and they didn't consult the opposition and the coordinating committees inside Syria. I think that the formation of the Syrian Revolution General Commission [SRGC] came at the right time to block all those opposition forces.

The SRGC is a newly formed coalition of more than 40 revolutionary groups inside and outside Syria that sees the "need to unite the field, media, and political efforts" and "the necessity of joining all efforts in one work front merging all visions." Referring to the initiatives to form national councils outside Syria, the SRGC also stressed that any representative project should be postponed, and called for working towards consensus across the spectrum of Syrian society.

WITH THE Syrian opposition divided, the U.S., European governments and their regional allies are seizing the moment to try to mold the outcome of the struggle to their liking.

At first, the U.S. offered only limited criticism as Assad tried to crush the protests. Instead of calling for him to step down, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton called Assad a "reformer." But as the revolutionary movement grew, the U.S. concluded that Assad would sooner or later lose power--and the continuing bloodshed made it impossible to dress him up in reformers' clothing any longer.

So, having rejected a Libya-style military intervention as too risky politically and prohibitively expensive, the U.S. settled on a strategy of regime change without revolution. By ratcheting up economic sanctions and isolating Syria diplomatically, Washington is hoping to pressure sections of the regime to push Assad aside and allow the opposition to take part in some kind of limited democratic transition.

That's why Saudi Arabian King Abdullah could denounce the Syrian "killing machine." This was more than ironic, considering that the Saudi regime is orchestrating a killing machine in neighboring Bahrain, where a Saudi-aligned Sunni monarchy is carrying out assassinations, mass arrests and torture to suppress the democratic mass movement that erupted after the Tunisian and Egyptian revolutions.

While the Saudi regime has long had tensions with Syria, it had been quiet until recently, apparently fearing that Assad's downfall could bring to power a popular government less willing to play by the rules--and one that could inspire challenges to the Saudi monarchy.

The Saudis, of course, are acting as a mouthpiece for their imperial sponsors in the U.S. Washington also was hesitant to call for Assad's ouster, not only because it worried about the domino effect of another Arab revolution, but because a democratic Syrian government might go beyond the anti-Zionist rhetoric of the Assad regime, press for the end of Israel's occupation of Syria's Golan Heights, and give a boost to the Palestinian national struggle.

So it instead relied on a carrot-and-stick approach to pressure Assad. As left-wing journalist Jim Lobe pointed out, until August 20, the Obama administration had

declined to call explicitly for Assad to step down for a variety of reasons, including a combination of hopes that he would follow through on his many promises to carry out far-reaching reforms and of fears that his departure would set the stage for even greater bloodshed and possibly sectarian civil war.

The U.S. is also trying to mold Syrian events through Turkey, which has separate but overlapping interests with the U.S. in the region.

Turkey, like the U.S., was initially reluctant to break with Syria, with which it has $2.5 billion in annual trade. In June, journalist Barbara Slavin summed up the view from Washington and the Turkish capital of Ankara: "Neither wants the Assad regime to fall, but both worry that the regime is not capable of positive change."

But the scale of repression along the Turkish border, which led to thousands of refugees crossing into Turkey, led Prime Minister Recep Erdogan to criticize the regime and host meetings of opposition leaders. In early August, Erdogan even referred to the Syrian crisis as an "internal affair" for Turkey--a reference to Syria's status as a province of the Turkish Ottoman Empire until 1918, and a calculated diplomatic provocation and vaguely military threat.

As a NATO member, Turkey is integrated into the U.S. and European military command structure. But an all-out NATO intervention is highly unlikely. Instead, Turkish troops could move across the border of what was their former colonial province with the stated aim of protecting refugees, some 7,000 of whom are still in Turkey following a Syrian military offensive against border towns several weeks ago.

Turkey is also engaged in a regional economic and political rivalry with Iran, which has maintained an alliance with Syria since the 1979 Iranian Revolution brought an Islamist government to power. At issue is whether Turkey's growing economic clout in Syria will trump Iran's longstanding strategic ties in Damascus. Both Syria and Iran support Hezbollah in Lebanon, a combination that has often thwarted U.S. and Israeli aims in the region.

Whatever their outcome, machinations in Ankara and Washington won't bring liberation to Syria. Both would prefer continued rule by a Syrian strongman with some "democratic" trappings like elections--rather like Hosni Mubarak's Egypt. And any help that Washington provides will come with strings--or rather, chains--attached that tie Syria to the U.S. aim of continued domination of the Middle East and the maintenance of Israel as a local enforcer of imperial power.

For the left in Syria's opposition, the challenges are great. The alliance of various groups in the councils can't substitute for an appeal to the working class that cuts across religious, tribal and regional lines. It was working-class struggle that tipped the balance in the Egyptian Revolution, adding economic and social weight to the mass movement in Tahrir Square.

The potential for a similar struggle exists in Syria, where hundreds of thousands of people have risked their lives in mass protests for nearly six months. It is out of that struggle that organization and leadership can emerge to overthrow the regime and open the way for even greater social and political transformation.