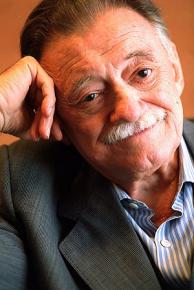

Uruguay’s incorruptible poet

mourns the death of celebrated Uruguayan writer Mario Benedetti.

ON MAY 17, the great Uruguayan writer Mario Benedetti passed away at the age of 88. His death was widely mourned in Latin America and Europe. In the U.S., it did not register at all.

This is unfortunate, indeed, for Benedetti was one of the most brilliant writers humanity has produced. He excelled in a wide range of literary genres: poetry, novels, short stories, essays, plays, screenplays and journalism. There are very few writers in history about whom this claim can be made. Yet in this country, it is as if he was never born, he never wrote, and he never existed.

In the meantime, the headlines of the past month have been preoccupied with Patti Blagojevich's circus act in the TV show I'm a Celebrity...Get Me Out of Here or the health saga of Susan Boyle (I proudly confess that I don't have the faintest idea who she is). This makes me sad. The reader may or may not forgive my chutzpah, or my ignorance, but I can't remember any U.S.-born writer that was as talented in such a versatile way as Benedetti.

Perhaps the U.S. establishment intentionally ignored him because of his adamant and uncompromising willingness to denounce U.S. imperialism.

Another great Latin American writer, Eduardo Galeano--whose Open Veins of Latin America was recently given by Venezuela's Hugo Chávez to Barack Obama for enlightening summer reading--was asked by the press how he felt about Benedetti's death. He simply had no words to articulate his feelings and asserted instead that "sorrow is expressed with silence."

Benedetti was the recipient of dozens of international awards and honors, having published more than 80 books that were translated into 19 languages. He began his writing career in 1945 and for years worked in Montevideo, Uruguay's capital, in a variety of jobs, such as typist, cashier, librarian, salesman, translator and many others.

Many of his poems were turned into songs by prominent Ibero-American folk singers such as Joan Manuel Serrat, Daniel Viglietti, Pablo Milanés and Nacha Guevara. Two of his most prominent novels were turned into movies, La Tregua (The Cease Fire) and Gracias por el Fuego (Thanks for the Fire).

His identification with the vicissitudes of ordinary people, his eloquent denunciation of injustice, government terror and U.S. imperialism was brilliantly reflected in his works, which were taken by people internationally as a source of inspiration and a battle cry.

For this, he paid a heavy price, being forced into exile after the 1973 military coup in Uruguay, having to flee Argentina after its own coup in 1976, moving back and forth many times between Europe and other Latin American countries and having friends murdered by the Uruguayan dictatorship.

IN HIS play Pedro y el Capitán (Pedro and the Captain) Benedetti presents a powerful denunciation of the inhumanity of the military dictatorships. In this work, the Captain and Pedro, interrogator and tortured leftist prisoner, exchange roles by the end of the play. The Captain psychologically collapses and begs Pedro for a crumb of information that he can use to justify his life role.

Iranians are famous for their love of poetry. Workers, peasant activists and rebellious youth in Latin America have also gravitated toward poetry and music for sustenance. These have helped us survive the days in which the toll is too heavy. And when the struggle moves forward, our collective voices have resonated with those thunderous words and melodies that our incorruptible bards sowed in our souls.

Taking nothing from our great poets, such as César Vallejo, Roque Dalton, Ernesto Cardenal, Antonio Machado and many others, it was Benedetti who fed me best. For he wrote about love, hope, anger, injustice and retribution with the eloquence of a great poet and the humbleness of a simple man.

In his poem "Dactilógrafo," he contrasts the alienation typical of the stuffiness and sterility of office work with the humanity and hopes of the typist. He does this with his remembrances of youthful, joyful times against the backdrop of a soulless business letter. Here is an excerpt:

Montevideo quince de noviembre

de mil novecientos cincuenta y cinco

Montevideo era verde en mi infancia

absolutamente verde y con tranvías

muy señor nuestro por la presente

yo tuve un libro del que podía leer

veinticinco centrímetros cada noche

y después del libro la noche se espesaba

y yo quería pensar en cómo sería eso

de no ser de caer como piedra en un pozo

comunicamos a usted que en esta fecha

hemos efectuado por su cuenta...Montevideo November fifteenth

nineteen fifty five

Montevideo was green in my childhood

absolutely green and with street cars

our dear sir by these means

I had a book of which I could read

twenty five centimeters every night

and after the book the night became thicker

and I wanted to think how could it be

not to be like a rock falling down a well

we inform you that as of this date

we have processed from your account...

Bertolt Brecht's phrase about the indispensability of those men and women who struggle all their lives--in contrast to those who quit at one point or another--was made famous in Latin America by Cuban composer and folksinger Silvio Rodríguez. Benedetti confronted this same subject in 1967 with his poem "Mejor te Invento" ("I'd Rather Invent You").

Many of us lived through the crisis that engulfed the international left after the emergence and fall of the Polish workers movement Solidarinosc in the early 1980s. We saw how comrades distanced themselves from the struggle and were eventually absorbed by the establishment into comfortable lifestyles. Against this experience, the poem represented an admonition to never give up. It also allowed us to cope with the loss of our former comrades.

I printed and framed it, and keep it in my office, and periodically look at it when remembering my "fallen" comrades. To this date, it reverberates through me as I watch the economic and military devastation unleashed by our rulers all over the world:

...Pero yo, te confieso, prefería

(¿cómo querés, hermano, que te hable?)

cuando tu vieja angustia estaba al día

con la angustia del mundo, cuando todos

éramos parte de tu melancolía...

inventarte es mi forma de creerte....But, I confess, preferred

(how'd you like, brother, that I speak to you?)

when your old anguish was up to date

with the world's anguish, when all of us

belonged to your melancholy...

inventing you is my way of believing in you.

I thought that Benedetti would always be with us, reassuring us of the certitude of our convictions and the righteousness of our struggle. While his last work "Biografía para encontrame" ("Biography to find myself") was not finished, yet his writings are now complete.

His work will be with us, but his prose and poetry can no longer anticipate our sentiment. What a loss. Not only for me. Not only for Latin America. But for the whole world.

Here, in the belly of the beast, we could do very well to share him with his strangers. The simple and humble working men and women of this country will need his incorruptible form of soul sustenance for the exacting battles that will rage in our not too distant future for a better world, a decent world, a world of justice.