Preserving minority rule in California

California teacher analyzes the reasons for the demise of a proposed ballot measure that would have made it possible to raise taxes on the rich.

CALIFORNIA'S RECESSION has been ugly, even more so than other states hit hard by the crisis. The unemployment rate is nearly one-third higher than the national average. In Los Angeles County alone, more than 600,000 people are out of work.

It's been a long road to the miserable spot we're in today. But the elephant in the room is how California's non-democracy is making the situation far worse than it could be--and once again, California's citizens won't have any say in the matter this November.

That's because the proposed California Democracy Act is dead on arrival.

Back in 1978, voters approved Proposition 13, which caps property taxes and requires a two-thirds vote to raise taxes or adopt a state budget. That lets a minority of the state legislature block attempts to raise taxes on the rich in order to maintain services.

It also means that California almost never adopts a budget on time--and in periods of declining revenue, the legislature defaults to cutting services to overcome the budget shortfall. Last year saw the loss of 16,000 teachers across the state, with at least as many pink-slipped again this year.

Sensing a historic opportunity to do away with the consequences of Prop 13, UC Berkeley linguistics professor George Lakoff proposed the California Democracy Act, which read simply: "All legislative actions on revenue and budget must be determined by a majority vote."

These 14 words would erase a good chunk of Prop 13 and further marginalize the state's Republican Party, which only has any relevance because of its veto power through Prop 13.

The trouble is that there's almost no chance that the California Democracy Act will obtain the 700,000 signatures necessary to end up on the November ballot as a referendum.

Campaigns usually bankroll a professional signature-gathering firm to do this heavy lifting, to the tune of $1 million. Lakoff hoped for a grassroots movement instead, counting on an angry electorate fired up over Wall Street misdeeds and the state budget crisis. The campaign would go viral, the Lakoff team predicted, once people realized that this was such a good idea.

One day after the deadline for signatures passed, George Lakoff e-mailed his supporters announcing that he had withdrawn the petition to get the measure on the ballot.

The campaign had faced a number of challenges. The first setback came when Secretary of State Debra Bowen ruled against accepting electronic signatures, a blow to an effort that hoped to use social networking to quickly (and cheaply) gather most of the signatures.

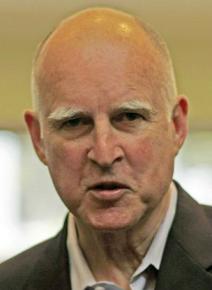

The main culprit, though? Liberal bloggers are pointing their fingers at state Attorney General Jerry Brown, who is also running for governor. Brown reworded Lakoff's initiative, replacing the word "revenue" with "taxes." Polling by David Binder Research showed overwhelming support for the original wording of the act, and substantial opposition to the attorney general's new formulation.

Lakoff cited the rewording in his e-mail acknowledging defeat. "At present," Lakoff wrote, "many of those who volunteered and have signed the petition for the first version are joining me in writing to the attorney general for an accurate title and summary. If we get an accurate title and summary this time, we will seek funding for a professional effort on the second round."

Best known for his book Don't Think of an Elephant, which coaches liberal politicians about learning from Republicans in how they articulate their messages, it's no surprise that Lakoff lays the blame for this defeat on semantics.

But Jerry Brown is right: Where else will new revenues come from, if not from taxes?

Supporters of the California Democracy Act tried to duck the issue of taxes instead of confronting it head-on with a clear-eyed "tax the rich" message. So when Brown called them on their bluff, the effort blew up in their faces.

Lakoff and the liberal bloggers are probably right that Brown was personally hostile to the Act. But the point is that they set themselves up to be defeated.

BUT THERE'S a more fundamental reason that the California Democracy Act failed to reach the ballot--more significant than a single vindictive politician nor any rewording.

Simply put, California's liberal establishment gave it the cold shoulder and watched it die.

For example, the California Teachers Association (CTA) waited so long to endorse the Act that it was practically useless when the union finally did get around to it, just two weeks before the deadline for signatures.

Everyone expected Republican hostility, but the Democratic Party got in on the act, too, by refusing to endorse the Act.

Its chair, former legislator John Burton, proposed a watered-down alternative instead that allows for the state budget alone to pass with a simple majority vote--meaning that the Democrats could get a budget passed by a majority...so long as it precludes any new taxes.

Why would the liberal establishment turn down an offer to expand its own power?

The CTA, which is bleeding members and money, is afraid of its own shadow. Its leadership relies on polling results to steer it toward whatever low-hanging fruit seems within grasp. There's a fear that tackling Prop 13 will bring out the wrath of the right wing and the business community.

The state's Democratic Party operates on the same principle. Its leaders are afraid of any initiative that might mobilize right-wing voters in opposition, and make their chances worse in the November governor's race--pitting Brown against former eBay CEO and right-wing nut Meg Whitman.

The Democratic Party is also very comfortable with the status quo that allows them to blame the two-thirds rule and the Republicans for all of the cuts to education and social services over the past few years--while avoiding any tough votes and difficult campaigns that would disrupt their cozy relationship with business.

Eliminating the two-thirds requirement would pose some uncomfortable issues to the Democratic Party: Is it prepared to take ownership over this crisis? Is it ready to raise taxes on the wealthy? The answer is no on both counts.

Last spring, the Democrats' "budget fix" included raising regressive taxes on working people and expanding corporate loopholes under the guise of "economic stimulus." Their pro-business rhetoric isn't as heated as the Republicans, but the Democratic Party is certainly still a "responsible" party of big business.

Even if Lakoff and his team had found a way to put the Act on the ballot and win over the electorate in November, there's no telling what liberal politicians would have done with any new powers to stick it to California's wealthiest citizens and businesses.

The California Democracy Act would have been an important extension of democracy, but its failure points to an even larger set of problems: the domination of the two-party system in California politics, like in the rest of the U.S.

Being clear about this is important in strengthening other reform movements down the road. In this case, blaming the choice of words is pinning the tail on the wrong donkey.