The sunshine of his accomplishment

, and pay tribute to a great artist whose politically charged poetry and music gave voice to our movement.

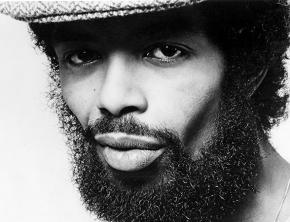

WE LOST one of the more brilliant minds and powerful voices for freedom last weekend. Gil Scott-Heron, the musician and spoken-word legend, died on May 27 in New York City at the age of 62.

Many of the articles written about his passing reduced his life to his struggle with drug addiction, and his massive body of work over 40 years to a single piece, "The Revolution Will Not Be Televised." But all of Scott-Heron's music and poetry should be celebrated--and he deserves to be remembered as one of the most powerful voices of the Black freedom struggle.

Born in Chicago in 1949, Scott-Heron spent his childhood with his grandmother in Tennessee. It was there that Scott-Heron became enamored with Langston Hughes, one of the great Black writers of the Harlem Renaissance. After his grandmother died when he was 12, Scott-Heron moved with his mother to the Bronx. There, he was recruited to attend the Fieldston School, a private prep school, where he was awarded a full scholarship for his exceptional abilities as a writer.

Scott-Heron attended college at Lincoln University, a historically Black college in Pennsylvania that Hughes had attended four decades before. He took time off to write two novels, The Vulture and The Nigger Factory, both of which received acclaim.

But Scott-Heron would become best known for his poetry and music--a unique, percussion-driven blend of jazz, blues and soul serving as the setting for his words, spoken or sung, but always powerful and politically charged.

He became an important voice of the Black Power era that shaped him. On the liner notes of his first album, Small Talk at 125th and Lenox, Scott-Heron listed Malcolm X, Black Panther Party cofounder Huey P. Newton, and musician Nina Simone as among his influences.

GIL SCOTT-Heron's stories, poems and songs are rich with contempt for racism and for the institutions of American power. A favorite target was the hypocrisy of northern liberals who decried the racism of the Jim Crow-era South while ignoring the poverty, police violence and discrimination that Blacks experienced in the North.

But Scott-Heron also turned his critical eye on Black America, challenging powerful institutions of the African American community such as historically Black colleges, and aspects of Black culture that undermined unity in the face of a hostile society. He mercilessly skewered Blacks who rose to prominence as political moderates--like, in "The Revolution Will Not Be Televised": "Roy Wilkins strolling through Watts in a red, black and green liberation jumpsuit that he has been saving for just the proper occasion."

Scott-Heron was especially moving in his depiction of the destructive toll that drugs took on the Black community. Tragically, Scott-Heron battled his own drug addiction, struggling under the weight of the brutal society that he resisted.

While Scott-Heron's art spoke most directly to the oppression that he experienced intimately--racism--he turned his fire against other forms of discrimination and injustice. Songs like "Who Will Pay Reparations on My Soul" expressed solidarity with indigenous peoples of the Americas. In 1979, Scott-Heron performed his song "We Almost Lost Detroit" at the No Nukes concert at Madison Square Garden in protest of nuclear energy.

His "Three Miles Down" is an anthem of solidarity with labor--mineworkers in particular. The words from a 1978 album will remind labor activists today of the April 2010 mine disaster that killed 29 workers in West Virginia:

Damn near a legend as old as the mines

Things that happen in the pits just don't change with the times.

Work till you're exhausted in too little space.

A history of disastrous fears etched on your face/

Somebody signs a paper everybody thinks is fine

But Taft and Hartley ain't done one day in the mines.

You start to stiffen. You heard a crackin' sound.

It's like workin' in a graveyard three miles down.

More recently, Scott-Heron cancelled a show in Tel Aviv during a 2010 tour in solidarity with the Palestinian boycott of Israel, stating he wouldn't play in Israel "until everyone is welcome there."

Scott-Heron's work had an immense influence on poetry and music. His particular approach to spoken-word and the integration of it with music was seminal in the birth of hip-hop.

Public Enemy's Chuck D attested to his stature with his Twitter comment in response to Scott-Heron's death: "RIP GSH...and we do what we do and how we do because of you." Kanye West's recent album My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy closes with what is both a tribute to Scott-Heron and essentially a remix of his poem "Comment #1 (Who Will Survive in America)"

Scott-Heron himself was more skeptical about his music's connection to hip hop. He preferred the description "bluesologist" and believed his singing/spoken-word style reached back into the blues tradition.

However it's categorized, though, there's no denying the power of Gil Scott-Heron's work--and its painful relevance today. Listening to some of his pieces from the 1970s, you could think he's talking about 2011--like "We Almost Lost Detroit," which is about the ever-present threat of nuclear disaster and eerily speaks to the Fukushima catastrophe in Japan:

Just thirty miles from Detroit

Stands a giant power station.

It ticks each night as the city sleeps,

Seconds from annihilation.

But no one stopped to think about the people

Or how they would survive,

And we almost lost Detroit

This time.

As beautifully and bitterly as Scott-Heron described and attacked the experience of racism and oppression, he also lovingly celebrated the contributions of Black activists and artists in creating a more livable world.

His fast-paced and brilliant poem "Ain't No New Thing"--recorded for his Free Will album accompanied by flute and percussion--is a scathing indictment of a society that exploits and oppresses Black people and then appropriates Black music, literature, art and culture. In it, Scott-Heron names Black artists such as Billie Holiday, Charlie Parker and Jimi Hendrix and proclaims that they:

...will live on!

And on and on in the sunshine of their accomplishments,

The glory of the dimensions that they added to our lives.

Gil Scott-Heron, too, will live on. His contributions to art and radical politics will not be forgotten, and his legacy will far outlive his too-short life.