Understanding the united front

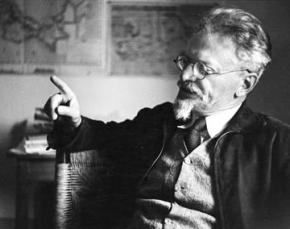

, author of The Meaning of Marxism, explains how revolutionaries developed a method for forging unity in action to meet the needs of the struggle.

IN THE wake of the 1917 Russian Revolution, when the working masses of Russia toppled an age-old autocracy and replaced it with a government of workers, soldiers and peasants' councils, momentous class upheavals shook Europe and other parts of the world. "The whole of Europe is filled with the spirit of revolution," wrote British Prime Minister Lloyd George.

In 1919, after both the October Revolution and the fall of the Kaiser in Germany at the end of 1918, revolutionaries believed that the European revolution was imminent. At this time, wrote the Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky, "many of us reckoned--some more, others less--that the spontaneous onset of the workers and in part of the peasant masses would overthrow the bourgeoisie in the near future. And, as a matter of fact, this onset was truly colossal. The number of casualties was very large. But the bourgeoisie was able to withstand this initial onset and precisely for this reason regained its class self-confidence." Capitalism was able to stabilize itself, at least temporarily.

The outbreak of the First World War had revealed the rot at the heart of the socialist movement--the majority of its leaders capitulated to the war aims of their respective governments. The success of the Russian Revolution accelerated the consolidation of new revolutionary organizations and parties of those leftists who split from the opportunist Social Democratic parties and remained committed to working-class internationalism and revolution. Though small at first, these parties grew, particularly in Germany and France, into mass parties.

None of them, however, had the size, implantation and experience necessary to lead mass workers' movements to success in the way the Bolsheviks had done in Russia. Whereas in Russia, the Bolshevik party had years to grow and develop in the context of intense class struggles, these new communist parties, formed in the midst of revolutionary upheaval, had existed for a matter of months.

These organizations--members of the newly founded Communist International--found it difficult going to chart the waters of mass political work. They were caught between the need to win over the majority of the working class, which still supported the old social democratic parties, while retaining the allegiance of impatient young radicals who had broken with the parliamentary politics and gradualism of Social Democracy, and wanted revolution now.

For the radicals, known as the "lefts," who essentially gave theoretical expression to revolutionary impatience, the goal of communists was to take action that "galvanized" or provoked the masses into action behind them. In Germany, this became known as the "theory of the offensive."

The lefts rejected alliances with the reformist Social Democrats to engage in struggle, since the latter were betrayers of workers' interests. Their attitude was to appeal over the heads of the reformists, directly to the masses--by taking resolute action, the masses would decide to follow them, they believed. This method was sometimes referred to as the "united front from below."

This approach in Germany culminated in the disastrous "March Action" in 1921, in which the Communist Party (KPD), responding to a police provocation by the government against miners in the country's central region, called a general strike. In conditions that called for defensive measures, the Communists proclaimed a revolutionary offensive, even using force--as well as manufacturing fake attacks that appeared to come from the right wing--to push reluctant workers into joining their hastily called and poorly prepared action.

The action ended in defeat and resulted in half of the KPD's membership, 200,000 people, quitting its ranks. In an assessment of the March disaster, Trotsky wrote:

The revolutionary and dynamic minority of the proletariat found itself counterposed in action to the majority of the proletariat, before this majority had a chance to grasp the meaning of events. When the party ran up against the passivity and dilatoriness of the working class, the impatient Communist elements sought here and there to drive the majority of the workers into the streets, no longer by means of agitation, but by mechanical measures...

[W]en the crushing majority of the working class has no clear conception of the movement, or is unsympathetic to it, or does not believe it can succeed, but a minority rushes ahead and seeks to drive workers to strike by mechanical measures, then such an impatient minority can, in the person of the party, come into a hostile clash with the working class and break its own neck.

IT WAS in these conditions that the united front tactic became an important topic of debate and discussion in the revolutionary movement.

First developed by German communists--strangely enough, before the March Action--the united front tactic involved proposing joint agreements with trade union and reformist leaders for the purposes of united action in defense of workers' interests. It was seen as a way to build unity in struggle--and, at the same time, force the reformists to account for themselves in front of the class and demonstrate the superior organizational, political and tactical skills of the communist workers in championing the united defense of working-class interests.

In an article written in 1921 on the united front, Trotsky outlined three basic forces in the workers' movement: the Communist Party, which "strives toward the social revolution and precisely because of this supports concurrently every movement, however partial, of the toilers against the exploiters and against the bourgeois state"; the reformists, who wish to make compromises with the system, but in order to retain a mass following are sometimes "compelled to support the partial movements of the exploited against the exploiters"; and, finally, the "centrists," who vacillate between these two.

To the argument that communists could call for united fronts "from below"--that is, to reject formal cooperation with union leaders and reformists by appealing directly to workers--Trotsky replied:

If we were simply able to unite the working masses around our own banner or our own immediate slogans, and skip over the reformist organizations, whether party or trade union, that would, of course, be the best thing in the world. But then, the very question of the united front would not exist in the present form.

The working-class in its day-to-day struggles strives, or senses, the need for the utmost unity in action. "Any party," Trotsky warned, "which mechanically counterposes itself to this need of the working class for unity in action will unfailingly be condemned in the minds of the workers."

Whereas reformists dread a rising mass movement for fear that it might get out of their control, and constantly seek ways to restrain it and draw it into safe channels, revolutionaries welcome this. "[T]he greater is the mass drawn into the movement," wrote Trotsky, "the higher its self-confidence rises, all the more self-confident will that mass movement be and all the more resolutely will it be capable of marching forward, however modest may be the initial slogans of struggle." Mass struggle radicalizes its participants and draws them toward revolutionary politics.

To create such united struggle, however, it is necessary to propose specific agreements for action with reformist and trade union leaders. Such action would naturally have mass appeal in the ranks of the reformist parties and organizations, and should the leaders of these organizations refuse to join forces, the onus would be on them for standing the way of united struggle. "We are," Trotsky wrote, "apart from all other considerations, interested in dragging the reformists from their asylums and placing them alongside ourselves before the eyes of the struggling masses."

HOWEVER, BY making proposals or agreements for the purposes of joint action with reformist organizations, Trotsky argued, we do not thereby dissolve ourselves into the reformist organizations.

In entering into agreements with other organizations, we naturally obligate ourselves to a certain discipline in action. But this discipline cannot be absolute in character. In the event that the reformists begin putting brakes on the struggle to the obvious detriment of the movement and act counter to the situation and the moods of the masses, we as an independent organization always reserve the right to lead the struggle to the end, and this without our temporary semi-allies.

More than a decade later, in 1934, Trotsky argued against the kind of fraternal unity that buried differences and tied the hands of revolutionaries:

Temporary practical fighting agreements with mass organizations even headed by the worst reformists are inevitable and obligatory for a revolutionary party. Lasting political alliances with reformist leaders without a definite program, without concrete duties, without the participation of the masses themselves in militant actions, are the worst type of opportunism.

The "lefts" denounced the united front as a form of accommodation with reformism. But a refusal to form united fronts on the grounds that the left should not "sully" itself by association with reformists was in practice a form of accommodation. One cannot win masses of people away from reformism simply by criticizing it in articles. They must be given an opportunity, as Trotsky put it, to "appraise the Communist and the reformist on the equal plane of the mass struggle." Behind the fear of accommodation toward reformism "lurks a political passivity which seeks to perpetuate an order of things wherein the Communists and reformists each retain their own rigidly demarcated spheres of influence," Trotsky wrote.

In the early 1930s, as German fascism became a mass force, threatening to come to power and smash the working class, Trotsky again--this time in exile and hounded by the Stalinist bureaucracy that had arisen to rule over the ruins of the workers' state in Russia--penned a series of articles urging the German Communist Party to form a united front with Social Democrats in order to defend working class institutions against the fascist street gangs. The CP at the time refused, on the grounds that the Social Democrats were "social fascists," and therefore as bad, if not worse, than the Nazis.

The Social Democrats did not want to organize a mass resistance to fascism--they had to be forced to do so. But the CP, by refusing to push for a united front for the purposes of defending workers' interests and organization against fascism, took the pressure off of the Social Democrats and made it easier for them to be complacent, without losing the allegiance of their supporters.

In rejecting the call to form a united front, the CP both failed to create the united forces that would have been necessary to defeat fascism and failed to win over the majority of workers to communism. By their verbal radicalism and ultra-leftism, but practical passivity, the CP helped pave the way to Hitler's victory.

TROTSKY WROTE on the united front at a time when mass communist parties with strong roots in the working classes of Europe vied for influence with mass social-democratic parties with even larger working-class followings.

These conditions do not prevail today, and that means the method of the united front cannot be applied in exactly the same manner as Trotsky put forward. As Trotsky wrote in 1922: "In cases where the Communist Party still remains an organization of a numerically insignificant minority, the question of its conduct on the mass-struggle front does not assume a decisive practical and organizational significance. In such conditions, mass actions remain under the leadership of the old organizations which by reason of their still powerful traditions continue to play the decisive role."

Does that mean the question of the united front is irrelevant to us?

Though conditions are vastly different today--in the U.S., for example, there are no mass working-class parties of any type, let alone mass revolutionary parties as there were in the early 1920s in Europe--the methodology outlined by Trotsky remains very important for socialists.

Consciousness changes in struggle, and for the most part, that struggle is a struggle for economic and political reforms. Revolutionaries cannot counterpose themselves to the struggle for reforms, but must in fact prove themselves to be the best fighters, the most resolute and the most committed to carry the struggle to the end. It is only by struggling alongside activists whose politics are not yet revolutionary and working with them that will we be able to win them to socialist politics.

Meanwhile, as, in the vast majority of cases, a minority force in these political, social, and trade union struggles, socialists must seek allies willing to take the fight a certain distance. We must be willing to form temporary alliances, both formally and informally, with reformist organizations and leaders, for the purposes of struggle, though we retain our independent organization, publications and so on.

Any other policy cuts us off from the very struggle that radicalizes people and draws them closer to anti-capitalist conclusions.