A worldwide rebellion of the oppressed

In the fifth part of a SocialistWorker.org feature on the revolutionary politics and enduring relevance of Malcolm X, looks at Malcolm's last year before his murder and his political trajectory during that tumultuous time. Click here to see all the stories in the series.

FORCED OUT of the Nation of Islam on the pretext of his comments about the John F. Kennedy assassination, Malcolm X began a search for both religious and political clarity.

His rapid evolution--and his embrace of the revolutionary traditions of the left--would profoundly shape the Black Power movement that emerged following formal legislative achievement of civil rights. Although Malcolm was killed before he could fully develop his ideas, his defense of self-determination for African Americans and the necessity of self-defense from racist attacks have remained a touchstone for those who have continued the struggle for Black liberation and the social transformation of the U.S.

Malcolm's initial moves toward independence were halting. Only a relatively small number of Nation of Islam (NOI) members initially followed him out of the organization. One major blow came when the young boxer Cassius Clay, who had been close to Malcolm, joined the NOI and became Muhammad Ali.

Along with the psychological and emotional impact of the NOI's hostility and threats came financial pressure: Malcolm had been paid only a modest salary, and his home was in the NOI's name. He was the father of six children, and had no prospect of any regular income beyond speakers' fees at college campuses. He hovered around political events, trying to orient himself for the next phase of his life. It was at this moment--while in Washington to monitor a Congressional hearing--that he briefly met Martin Luther King for the first and only time.

Malcolm's first steps were to try to clarify where he stood in religious terms. With former members of the NOI and some others, he founded Muslim Mosque, Inc., which initially positioned itself within the NOI's theology. But Malcolm, finally free to explore orthodox Sunni Islam, set out, with a loan from his sister, to make the haj--the Muslim pilgrimage to Mecca. It was a transformative experience--enhanced by Malcolm's status as an official guest of the Saudi state.

During his trip, Malcolm concluded that NOI leader Elijah Muhammad's race-based conception of Islam was fundamentally wrong. As he put it in The Autobiography of Malcolm X: "[I]n the Muslim world, I had seen that men with white complexions were more genuinely brotherly than anyone else had ever been. That morning was the start of a radical alternation in my whole outlook about 'white' men." The haj marked Malcolm's final rejection of the NOI's version of Islam and an embrace of the Sunni mainstream.

Back in the U.S., Malcolm announced that Muslim Mosque, Inc., would be a religious organization, not a political one. In a few months time, he launched a political group, the Organization for Afro-American Unity (OAAU). Its politics, he said, would be Black nationalist:

Lee Sustar examines the politics of Malcolm X as they were shaped by the world of struggle around him—and their meaning for today's strugglesThe legacy of Malcolm X

The economic philosophy of Black nationalism is pure and simple. It only means that we should control the economy of our community. Why should white people be running all the stores in our community? Why should white people be running all the banks in our community? Why should the economy of our community be in the hands of the white man?

BY MOVING squarely into the political arena, Malcolm hoped to fill the vacuum that the NOI had created by its refusal to match its militant rhetoric with deeds. As he recalled in the Autobiography:

[P]rivately, I was convinced that our Nation of Islam could be an even greater force in the American Black man's overall struggle--if we engaged in more action. By that, I mean that I thought privately that we should have amended, or relaxed, our general non-engagement policy. I felt that, wherever Black people committed themselves, in the Little Rocks and Birminghams and other places, militantly disciplined Muslims should also be there--for all the world to see, and respect, and discuss.

It could be heard increasingly in the Negro communities: "Those Muslims talk tough, but they never do anything unless somebody bothers Muslims." I moved around among outsiders more than most other Muslim officials. I felt the very real potential that, considering the mercurial moods of the Black masses, this labeling of the Muslims as "talk only" could see us, powerful as we were, one day suddenly separated from the Negroes' frontline struggle.

Crucially, if Malcolm was moving toward the civil rights movement, the movement was also moving toward some of Malcolm's key conceptions, from his criticism of the Democratic Party--"show me a Democrat and I'll show you a Dixiecrat," Malcolm often said--to his rejection of nonviolence.

Young movement leaders also shared Malcolm's affinity for the newly independent countries in Africa and Asia. Thus, when Malcolm toured Africa in the spring of 1964, he happened to meet with activists John Lewis and Donald Harris of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in the Kenyan capital of Nairobi.

"The Nairobi meeting was followed by a series of attempts by Malcolm to forge links with SNCC," historian Clayborne Carson wrote in his book about SNCC. "Malcolm's Pan-African perspectives and his awareness of the need for Black self-defense and racial pride converged with the ideas gaining acceptance in SNCC." John Lewis would later recall that Malcolm, "more than any other single personality" had been "able to articulate the aspirations, bitterness, and frustrations of the Negro people," thereby "forming a link between Africa and the civil rights movement of this country."

SNCC activists and others were also drawn to Malcolm's critique of nonviolence as a principle in the movement. As Malcolm said his his first public speech for the OAAU on June 28, 1964:

Tactics based solely on morality can only succeed when you are dealing with people who are moral or a system that is moral. A man or system which oppresses a man because of his color is not moral. It is the duty of every Afro-American person and every Afro-American community throughout this country to protect its people against mass murderers, against bombers, against lynchers, against floggers, against brutalizers and against exploiters.

The murders of three civil rights workers--James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner--a few weeks later in the summer of 1964 could be seen as a confirmation of Malcolm's view. In fact, there was already an armed organization of Southern Blacks--the Deacons of Defense--who had quietly provided security for the civil rights movement for years. Many movement activists concluded that nonviolence might be a tactical necessity in the face of heavily armed Southern authorities, but it could also leave people defenseless against the police and the Ku Klux Klan, which often amounted to the same thing.

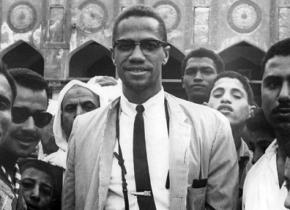

MALCOLM'S EFFORTS to influence the civil right movement was informed by his experience on a second foreign trip in 1964. He met with several heads of state who had been leaders in anti-imperialist or nationalist movements--Gamal Abdel Nasser of Egypt, Jomo Kenyatta of Kenya, Julius Nyere of Tanzania, Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana and Sekou Touré of Guinea Conakry.

The trip had a profound impact on Malcolm. In one of his last speeches, he described how imperialism had changed its methods, with the old colonial powers in Africa, the Middle East and Asia replaced by the U.S:

When you're playing ball and they've got you trapped, you don't throw the ball away--you throw it to one of your teammates who's in the clear. And this is what the European powers did. They were trapped on the African continent, they couldn't stay there--they were looked upon as colonial and imperialist. They had to pass the ball to someone whose image was different, and they passed the ball to Uncle Sam. And he picked it up and has been running it for a touchdown ever since. He was in the clear, he was not looked upon as one who had colonized the African continent.

At that time, the Africans couldn't see that though the United States hadn't colonized the African continent, it had colonized 22 million Blacks here on this continent. Because we're just as thoroughly colonized as anybody else.

Malcolm was killed before the countries he saw as models--Algeria, Ghana, Egypt--degenerated into military dictatorships. Moreover, he took the claims of those regimes to be socialist at face value, whatever the actual conditions of workers or peasants:

All of the countries that are emerging today from the shackles of colonialism are turning towards socialism. I don't think it's an accident. Most of the countries that were colonial powers were capitalist countries, and the last bulwark of capitalism today is America. It's impossible for a white person to believe in capitalism and not to believe in racism. You can't have capitalism without racism. And if you find one, and you happen to get that person into a conversation, and they have a philosophy that makes you sure they don't have this racism in their outlook, usually, their political philosophy is socialism.

As Ahmed Shawki put in his book Black Liberation and Socialism, Malcolm's "idea of socialism did not involve working class emancipation and workers' power, but rather saw socialism as synonymous with national independence and economic development. His uncritical stance toward the newly independent African regimes actually helped blunt the edge of some of his earlier formulations."

Nevertheless, Malcolm's experience abroad led him to question his previous political framework. "So I had to do a lot of thinking and reappraising of my definition of Black nationalism," he said in an interview with Young Socialist magazine. Malcolm pointed out that he had stopped using that term to describe himself. He also spoke out in favor of "women's freedom," a break from the Nation of Islam's conservative views.

Some have claimed that Malcolm had effectively become a socialist by the time he was cut down. While he did appear at forums organized by the Socialist Workers Party and linked capitalism to racism, the fact is that Malcolm's new politics hadn't crystallized.

Further, Malcolm rejected the socialist strategy of seeking to build political unity between Black and white workers. In a 1965 interview, Malcolm was asked if Blacks alone could achieve revolutionary change:

Yes. They'll never do it with working-class whites. The history of America is that working-class whites have been just as much against not only working Negroes, but all Negroes, period, because all Negroes are working-class within the caste system. The richest Negro is treated like a working-class Negro. There never has been any good relationship between the working-class Negro and the working-class whites...

[T]here can be no worker solidarity until there's first some Black solidarity. We have got to get our problems solved first, and then if there's anything left to work on the white man's problems, good, but I think one of the mistakes Negroes make is this worker solidarity thing. There's no such thing--it didn't even work in Russia.

MALCOLM'S CONTINUED emphasis on racial solidarity led to an ambiguity in his attitude towards Black politicians.

Although he viewed nearly all of the small number of Black elected officials of his day as co-opted, he believed that Blacks should step up efforts to elect independent political leaders. This was to be a task of OAAU. Malcolm also frequently pointed out that Black votes held the balance of power in presidential contests between the Republicans and Democrats--implying that Black voters could play the role of political kingmaker.

In a well known April 1964 speech, "The Ballot or the Bullet," Malcolm did explore the possibility of an electoral strategy--and broke from the NOI's abstention by coming out explicitly for the struggle for the right to vote.

Malcolm's biographer Manning Marable sees the speech as a definitive change. "What was most significant," Marable wrote, "was his shift from the use of violence to achieve Blacks' objectives to the exercising of the electoral franchise. By embracing the ballot, he was implicitly rejecting violence, even if this was at times difficult to discern in the heat of his rhetoric."

Marable's claim is unconvincing. The "Ballot or the Bullet" does hold out the possibility that the U.S. can have a bloodless revolution: "All she's got to do is give the Black man in this country everything that's due him, everything," Malcolm declared. "So it's the ballot or the bullet." But the direction of Malcolm's speech is that "everything due" African Americans went far beyond the right to vote to include other questions, like economic issues.

But Malcolm's ideas on how to achieve economic gains were, at this stage, little advanced from Elijah Muhammad's ideas of Black economic development, although he'd dropped the NOI's anti-Semitic portrayal of Jews as the economic predators of the Black ghetto.

The model for African Americans, Malcolm said, could be the Woolworth's dime store or General Motors, which both started small. "So our people not only have to be re-educated to the importance of supporting Black business, but the Black man himself has to be made aware of the importance of going into business," he said. Malcolm had no comment about where and how to get capital for such ventures--or the implication of Black bosses exploiting Black workers.

THERE WAS another, more immediate contradiction in Malcolm's "Ballot or the Bullet" speech. Finally using his powerful oratory to demand the right of African Americans to vote, he pointed out that Black votes had been decisive in winning the 1960 election for John F. Kennedy. Yet as Marable points out, Malcolm, while calling for the right to vote, concentrated his fire on both Republicans and Democrats:

I'm not a Republican, nor a Democrat, nor an American, and got sense enough to know it. I'm one of the 22 million Black victims of the Democrats, one of the 22 million Black victims of the Republicans, and one of the 22 million Black victims of Americanism. And when I speak, I don't speak as a Democrat, or a Republican, nor an American. I speak as a victim of America's so-called democracy.

You and I have never seen democracy; all we've seen is hypocrisy. When we open our eyes today and look around America, we see America not through the eyes of someone who has enjoyed the fruits of Americanism, we see America through the eyes of someone who has been the victim of Americanism. We don't see any American dream; we've experienced only the American nightmare. We haven't benefited from America's democracy; we've only suffered from America's hypocrisy.

Malcolm pointed out that the Democrats controlled both the White House and Congress, but still hadn't passed civil rights legislation:

Any time you throw your weight behind the political party that controls two-thirds of the government, and that party can't keep the promise that it made to you during election time, and you're dumb enough to walk around continuing to identify yourself with that party, you're not only a chump, but you're a traitor to your race.

Malcolm hammered the Democrats at every opportunity, showing how the northern leaders of the party were beholden to the racist "Dixecrats" who remained in office because of segregation. "Put the Democrats first, and they'll put you last," he said.

Nevertheless, Malcolm did make an exception for a handful of African American officeholders like Democratic Rep. Adam Clayton Powell Jr., the Harlem minister whom Malcolm regarded as an independent because of his frequent clashes with the party establishment.

In Manning Marable's view, this was an indication of Malcolm's move towards mainstream electoral politics.

Of course, it is impossible to know what attitude Malcolm might have had towards the wave of Black elected officials that emerged in the 1970s and 1980s, and the parallel expansion of the Black middle class. But it is by no means certain he would have joined this trend or celebrated it. Having long commented on the class tensions in Black America by contrasting the condition of the "field Negro" and the "house Negro," would Malcolm have pulled back from such a critique even as class differences among African Americans became more pronounced, and racial segregation and high rates of Black poverty remained?

Since Malcolm never had the opportunity to address the inconsistencies in his views, it is difficult to speculate. But given his stated turn towards a revolutionary perspective, it's impossible to make a convincing case that Malcolm was simply evolving towards Democratic Party politics when he was killed.

WHAT WE do know is that in the last weeks of his life, Malcolm was making a major effort to engage with the Southern struggle.

In the fall of 1964, Martin Luther King Jr., asked by a reporter about Malcolm's break with the NOI, said, "I look forward to working with him." Malcolm supported the fight for voting rights in Selma, Ala., traveling there to meet with representatives of civil rights groups to try to formulate a common strategy as the bloody confrontation--depicted in the recent movie Selma--finally forced President Lyndon Johnson to begin to move on voting rights legislation. Coretta Scott King, Martin Luther King's wife, met with Malcolm while King was in jail. "He wanted to present an alternative; that it might be easier for whites to accept Martin's proposals after hearing him," Coretta King recalled. "He seemed sincere."

Malcolm, after his long years outside the struggle because of NOI doctrine, was eager to get involved. Just a few months after the "Ballot or the Bullet" speech that espoused separate Black economic development as the foundation of African American advancement, Malcolm now maintained that the civil rights movement had to be seen as a part of global struggle.

"[In] my opinion, the young generation of whites, Blacks, browns, whatever else there is, you're living in a time of revolution, a time when there's got to be change," Malcolm said during his famous debate at Britain's Oxford University in December 1964.

The topic of the debate was "extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice; moderation in the pursuit of justice is no virtue," based on a famous quote from right-wing Republican Sen. Barry Goldwater, the GOP's presidential candidate in 1964.

Malcolm relished taking the affirmative side of the debate. "I don't believe in any form of unjustified extremism," he said. "But I believe that when a man is exercising extremism, a human being is exercising extremism, in defense of liberty for human beings, it's no vice."

He concluded: "People in power have misused it, and now there has to be a change, and a better world has to be built, and the only way it's going to be built is with extreme methods. I, for one, will join in with anyone--I don't care what color you are--as long as you want to change this miserable condition that exists on this earth."

MALCOLM WAS murdered on February 21, 1965, before his new approach to politics could bear fruit.

The murder came after months of invective and condemnation from the NOI. Malcolm's own brother Philbert had denounced him, reading from a script written for him by the NOI leadership. Louis X, Malcolm's Boston ally who would later become known as Louis Farrakhan, wrote a three-part article in the newspaper Muhammad Speaks under the headline "Malcolm's Treachery, Defection." Louis X at one point declared that Malcolm was "worthy of death." The NOI newspaper also featured a cartoon of Malcolm's head bouncing down the sidewalk to join other "traitors."

Ultimately, three members of the Nation of Islam went to prison for the assassination, committed in Harlem's Audubon Ballroom, although questions about the possible role of undercover police have lingered for years. Manning Marable's research found that the usual security precautions taken by the NYPD during Malcolm's events weren't followed that day.

No one in a position of authority has ever put much effort into finding out exactly what happened on that February day--but then again, the political establishment wasn't particularly sorry that Malcolm was no longer around.

It's impossible to easily summarize Malcolm X's political views when he was shot down--but three elements stand out: an uncompromising opposition to racism and imperialism, a determination to strip away the façade of U.S. democracy, and a commitment to Black self-determination as part of a wider revolutionary transformation of society, in the U.S. and internationally.

Malcolm was killed before he could develop those ideas into a political perspective or build an organization to advance them. Nevertheless, he had made an enormous contribution to the Black freedom movement in the U.S. A product of the African American working class, he had absorbed the history of his peoples' struggles and gave them a powerful, inspirational voice as the Black movement rose in the 1950s.

Malcolm helped to shape that struggle--and in turn, he was shaped by it. He posed the question that, half a century later, the Black Lives Matters movement has raised once more: Can Black liberation be achieved within the confines a system built on slavery and racism?

Just days before his death, Malcolm told a group of Columbia University students that it was "incorrect to classify the revolt of the Negro as simply a racial conflict of Black against white, or as purely an American problem. Rather, we are seeing today a global rebellion of the oppressed against the oppressor, the exploited against the exploiter."

With words such as these, Malcolm blazed a trail for the rise of Black revolutionary organizations such as the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense and the League of Revolutionary Black Workers--and the revival of the far left generally in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Malcolm's impact on those militants will be the subject of the final article in this series.