What I learned about Bernie Sanders

recalls her time as an intern for Bernie Sanders, in a contribution to the left's discussion of Sanders' campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination.

TO THOSE who have spent any significant amount of time in Vermont, it is clear that Bernie Sanders is widely beloved by his constituents. The support for "Bernie," as his supporters fondly call him, was clear on May 26 as thousands flocked to Sanders' presidential campaign kickoff rally on the edge of Lake Champlain in Burlington, Vermont.

The "People's Assembly," organized by a group including former Occupy Wall Street activists and environmentalists, spoke to a deepening anger felt by working-class Americans. Sanders, who is running as a Democrat, rightfully condemned the fact that "one family owns more wealth than the bottom 130 million Americans" and cited the Fight for 15 campaign as a source of inspiration.

In a political arena filled with the likes of war hawk Hillary Clinton and misogynist Ted Cruz, Sanders' words were a welcome departure from the mainstream. But despite Sanders' progressive rhetoric and the Occupy-esque excitement of his campaign launch, Bernie for President will only serve to pull dedicated activists out of movement work, away from building an independent alternative, and into the Democratic Party machine.

As a developing socialist, I, too, considered the possibilities of Sanders' political project when I went to intern for him in the summer of 2012. Although skeptical about calling Sanders a "socialist," I wondered whether he could be a vehicle for our side to fight back. And of course, I was eager to meet the man who hung a portrait of Eugene Debs (one of my own radical idols) on his wall.

I spent that summer in two alternate worlds. By day, I worked in Bernie's office clipping newspapers and writing letters to constituents, and by night I organized with the International Socialist Organization, building panel discussions about Palestinian liberation and fighting back against the basing of F-35 bombers by the U.S. military at Burlington International Airport.

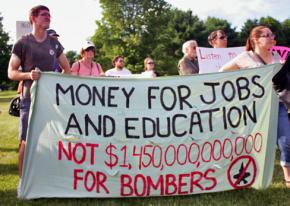

THE FIGHT around the F-35 came to define the political moment in Vermont that summer, with debate raging between activists fighting the imperial, economic and environmental consequences of the F-35s, and the Democratic Party operatives forcing the basing on the small Vermont town, with the full support of the Congressional delegation--including Bernie Sanders.

The basing of the F-35s promised to have devastating consequences for Vermonters, including plummeting home values and adverse health impacts that would disproportionately impact minority and low-income populations. This is not to mention the grotesqueness of the deal itself, with trillions of dollars being spent on aircraft meant to bomb foreign countries, instead of on schools, infrastructure or health care--a contradiction that one would assume Bernie would acknowledge.

But the lines were clearly drawn in Sanders' office. Constituent after constituent poured into the office to express dismay at the F-35 proposal, recounting stories of their home values being destroyed or of the terror that their child faced hearing bombers in school every day.

Most of the time, these concerns were dismissed as unserious by office staff--they were often characterized as the concerns of "anarchists" who couldn't possibly understand the art of politics. Bernie has no influence on military decisions, they kept repeating--these people just really don't get it.

In reality, Sanders' support for the basing of the F-35s was critical to the project's eventual success. Sanders had nothing to say about the burden that the basing would place on working-class Vermont families, and he didn't want to hear from constituents who said otherwise. As both an activist and an intern, I was forced to choose whether to stand with the people of Vermont or with a politician who remained out of touch with grassroots activism.

I ultimately found myself protesting my own boss at a Vermont Democratic Party fundraiser, dodging the gazes of my co-workers and putting my job on the line. This continuous tug between the two forces continued throughout the summer. I bit my tongue as I worked through ribbon cuttings and town halls, while struggling to remain involved in political organizing beyond Sanders and the Democrats.

I still looked to Sanders for a political lead, hoping to eventually understand his political end game. What did he have to say about the occupation of Palestine? What did he think of our continuing imperialist interventions in the Middle East?

Had I done my research, I would have discovered Sanders' frankly hawkish positions on foreign policy. It only takes a brief search to uncover his ardent support for Israeli apartheid, his repeated authorizations of funding for the U.S. military budget, and even his initial vote for Bush's original Authorization for Use of Military Force resolution that began the war on Afghanistan. I would have even discovered pictures in the local newspaper of activists I knew being thrown out of Sanders' office for protesting his support of the U.S. bombing of Yugoslavia.

Needless to say, Sanders was not the anti-imperialist, anti-capitalist folk hero I had hoped he would be.

IN DETAILING this experience, I aim not to raise the question of the purity of Sanders' politics or whether he represents the "perfect" political candidate. Those on the left can and should support candidates with whom they may not share agreement on every political issue, but with whom they can work to build an independent left that begins to challenge the hegemonic political structure.

Even before Sanders declared he was running as a Democrat in this presidential election cycle, he caucused with the Democratic Party in the U.S., hedging his bets on them as a vehicle for accomplishing change, despite the fact that the Democrats have never been anything but a party of the ruling class. When it comes down to it, Bernie does not stand on the side of the oppressed or exploited on principle, but only when it falls in line with his political project.

I can only speak to my own experience working in the office of Bernie Sanders, but after a few months, it became clear to me that electoral politics so closely tied to the Democratic Party could only be a dead end for those seeking revolutionary change. The experience was one of the key reasons I eventually joined the International Socialist Organization, which had a clear vision of working class self-emancipation.

My own experience is a miniscule example of the choices the left will face come next year, when Sanders throws his full support behind Hillary Clinton as the eventual Democratic presidential nominee, as he has every intention of doing. In the here and now, we must strategically decide the best way to spend our limited political capital. Principled activists who throw their political efforts into "Bernie for President" will find themselves orienting on the Democratic Party, rather than on the numbers of people who are beginning to come to radical conclusions.

The openings for radical politics in this moment are apparent, whether we throw ourselves into the nationwide rebellion against police brutality and racism, or join the fight in schools against standardized testing, or walk the picket line with striking oil workers. And of course, we must engage with those who are pulled to Sanders' message and offer them a much broader vision for the U.S. left--a left that fights on its own terms for working-class revolution. These are strategies that aim to build a left in the U.S. that has not existed for decades--an aim that Bernie Sanders, in practice, does not share.

As a friend recently reminded people on Facebook, using the words of Eugene Debs, "[I]f you are looking for a Moses to lead you out of this capitalist wilderness, you will stay right where you are. I would not lead you into the promised land if I could, because if I led you in, someone else would lead you out."

Ultimately, neither Sanders nor any other politician can lead us to the alternate society we fight for. We must build it for ourselves. It turns out that Sanders does have a picture of Eugene Debs in his office--though one can only imagine what Debs would have to say to Bernie today.