How Chicago schools went broke on purpose

breaks down how Chicago officials are using a budget "crisis" to help out their banker friends and advance their strategy of restructuring public education.

CHICAGO MAYOR Rahm Emanuel announced a new round of savage budget cuts for Chicago Public Schools (CPS) on July 1. Emanuel's proposal would eliminate $200 million from the CPS budget by implementing the following cuts, among many others:

Eliminate 5,300 coaching stipends for elementary school sports ($3.2 million);

Eliminate 200 special education positions rather than fill vacancies ($14 million);

Consolidate bus stops by having students report to a local area school in order to get transportation to a magnet school ($2.3 million);

Shift start times for some high schools 45 minutes later ($9.2 million).

The announcement came one day after the city made a $634 million payment into the teachers' pension fund just hours ahead of the deadline. Emanuel created waves of uncertainty in the run-up about whether the city would meet its obligation.

The anxiety provoked by the last-minute scramble should recall the infamous words of Emanuel speaking to a Wall Street Journal conference of CEOs in 2008 just weeks after Obama won his first White House term and tapped Emanuel as his chief of staff. "You never want a serious crisis to go to waste," said Emanuel as the yet-to-be-inaugurated administration stared in the face the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression of the 1930s. "This crisis provides the opportunity for us to do things that you could not do before."

As Emanuel's record as mayor since 2011 shows, if there's no crisis, then you may need to set up the conditions to create one. If that sounds too conspiratorial to be plausible, consider how the city of Chicago arrived at this moment when the CPS budget is facing a $1.1 billion shortfall.

Politicians and pundits alike moan about how the city's obligations to the teachers' pension fund, which will rise next year to $676 million, is pushing the system deeper into debt. But city officials can't be surprised about how we got here: Between 1995 and 2004, the city didn't make even one payment into the fund. During that time, the revenues that might have been used to keep the city's obligations were instead used to fund operations. So any "shock" about the size of the city's shortfall to the pension fund is a show for the cameras.

Between 2011 and 2013, CPS was granted a "pension holiday" that temporarily reduced the size of its payments, but didn't address the unfunded liabilities that kept piling up, thus delaying, but also deepening, the looming debt crisis facing the school system. The day after CPS made its required $634 million payment to the pension fund, Emanuel entered into talks with the fund to immediately borrow back $500 million--at 7.75 percent interest.

While that plan has been shelved, it provides a glimpse into how the city's financial mismanagement created a situation where a large portion of the revenues earmarked for CPS that should be headed to the classroom are instead directed toward debt service and pension obligations.

IF ALL of this shuffling of CPS debt and last-minute scrambling to repay loans, only to secure larger and more costly ones that don't resolve the underlying shortfall, rings a bell for SocialistWorker.org readers, it's because the European Union is forcing Greece into the same maneuvers.

But there's one crucial difference: Rahm Emanuel and the city's political establishment could have easily fixed the crisis they allowed to unfold.

"The City of Chicago has known that more money was going to have to go into the pension systems in 2015," said Ralph Martire, executive director of the Center for Tax and Budget Accountability, on July 1. "They had four and a half years to plan for it and they did nothing."

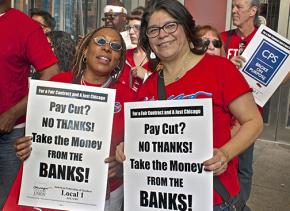

This is what's behind the Chicago Teachers Union's (CTU) claim that CPS is "broke on purpose."

According to Martire, CPS should be "front and center taking blame" for "using the pension system very much like a credit card, running up debt and deferring payment of it until now."

Enter Emanuel, with his latest scheme to resolve the budget crisis. Under his so-called "grand bargain," according to Rahm, "Everybody would have to give up something, and nobody would have to give up everything."

The state of Illinois would agree to pick up the "normal cost" of teacher pensions--that is, the amount of new benefits earned by teachers--for the next two years, while teachers would have to pay for their entire share of the contribution to the fund out of their paycheck.

The CTU explains that this would amount to an effective 7 percent pay cut for teachers--but combined with the budget cuts announced July 1, these measures would drive down the city's expenditures.

Emanuel is also proposing a property tax increase that would generate $225 million in additional revenue--which would mean about $225 more in annual taxes for the owner of a $250,000 home.

So how has the crisis provided Emanuel with an opportunity to do things he couldn't do before? For one, it has given him the political cover to wriggle out of his pledge not to increase taxes. Second, it enabled him to continue his frontal assault on the living standards of Chicago teachers. And of course, there's the massive bite of the proposed CPS budget--which amounts to Rahm kicking Chicago's students and parents in the teeth, once again.

BUT OF course, not everyone is giving up something, as Rahm claimed.

Property tax increases are regressive--they represent a higher proportion of total income for working-class people than for the wealthy. A progressive income tax, on the other hand, could generate revenue by taxing the 1 Percent and sparing those who are still reeling from the effects of the Great Recession.

The bankers continue to make a fortune from taking advantage of the city's dire financial circumstances. Every time Chicago repays a massive loan only to take out a new one, the banks collect huge transaction fees--and impose ever-higher interest rates as the city's credit rating falls.

The city could also have stopped bleeding piles of money by seeking to terminate or renegotiate a series of bad financial bets--in the form of arcane interest rate swaps--it agreed to a decade ago. According to a Chicago Tribune series exposing these toxic financial deals, the city stands to lose $100 million on its risky--and ultimately losing--bets. Though school districts and cities across the U.S. made similar bad deals, CPS made larger gambles than any other school district.

Several cities have sued banks for failing to fully disclose the risks and won major settlements. The cities of Houston and Modesto, California, for example, each recently won $2 million in compensation. CPS, however, won't be winning any such award. It missed the six-year window to file a complaint with the regulatory board that could have granted such relief.

But what looks like "mismanagement" from afar is more likely a case of cronyism. After all, the CPS board president is David Vitale, former vice chairman and director at Bank One Corp. He presided over these deals as CPS's chief administration officer and then its chief operating officer, and his friends in the banking sector are the ones who benefit.

Now the underhanded logic of Rahm's re-election campaign should be plain to see. When he said that he was the only one with the necessary experience to get Chicago out of its looming budget crisis, he meant that he had experienced friends in the banking sector who would benefit from revolving the city's debt and continuing massive borrowing at high interest rates--and he had enemies in the public sector to punish by making cuts in school budgets and teachers' compensation.

LIKE IN Greece, the pound of flesh extracted from public-sector workers and Chicago parents and students is being handed to the loan sharks and vultures who see Chicago's budget deficit as an opportunity to earn handsome interest payments on loans that only further plunge the city into a debt trap, generating the potential for more loans at even-higher interest rates, and on and on.

The Foundation for Economic Freedom, a libertarian think tank that never met a government program it didn't want to ax, has nevertheless provided a clear description of what it calls "Rahm's Rule of Crisis Management":

Rahm's Rule is a useful accessory to a body of theory that seeks to explain the political economy of regulation. The rule tells us that major crises can provide cover for distributing benefits to targeted special interest groups. The greater the magnitude of a given crisis and the shorter the interval for forming legislation to deal with it, the larger the spread of pork that can be packed into the final legislation. Rahm's Rule is a guarantee that efforts to resolve a deadline-based crisis will go on to the very last minute...

Doing all this in the full light of day and with full and open debate would be a challenge. But then there are crises to serve the politicians' interests. Some arise spontaneously and some are created or magnified consciously by the politicians themselves.

Yet Rahm's drive to offload the brunt of the budget shortfall onto teachers sets up the potential for another confrontation with the CTU, three years after a nine-day teachers' strike dealt Rahm one of the most significant political defeats of his career.

Chicago has the option to tap revenue sources that Greece doesn't. But that will require a mobilization of sufficient strength by those with a stake in ending this debt treadmill--the teachers and paraprofessionals of the CTU, and the working-class families of Chicago whose children attend CPS schools--to force Rahm and his cronies to abandon the corporate cash that keeps the whole nausea-inducing ride churning out opportunities for bankers and spitting out the rest of us.