Hearing the voices of those bearing the brunt

reports from Austin, Texas, on the discussions and presentations at the annual convention of the Campaign to End the Death Penalty.

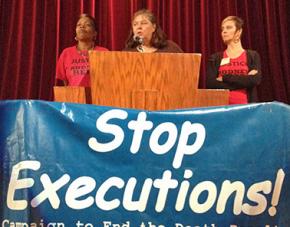

MORE THAN 60 people gathered for the Campaign to End the Death Penalty's (CEDP) annual convention, held in Austin, Texas, in mid-November.

The CEDP was formed 20 years ago to challenge the most barbaric aspect of the U.S. criminal injustice system: capital punishment. It has stood out from other anti-death penalty and criminal justice reform organizations because it has put death row prisoners and their families at the center of the struggle, emphasizing the humanity of the victims of this system. This year's convention was no different.

Lawrence Foster, the 87-year-old grandfather of Kenneth Foster Jr., who faced down the death penalty in Texas in 2009, gave the opening remarks for the conference. Standing before us in his casual blazer and gray Chuck Taylors, his presence reminded us what is possible.

His grandson Kenny was charged under the unjust "law of parties" law in Texas, which makes defendants who are merely present when a crime is committed just as culpable as the person who committed it. So even though he was in his car with the windows rolled up when someone was shot and killed, Kenny was charged along with the shooter and given the death penalty.

In 2007, he came within six hours of being executed before his sentence was commuted to life. Lawrence Foster was a tireless fighter for his grandson the whole time, speaking at press conferences and demonstrations and helping to organize various events to mobilize the public behind the call to save Kenny. But the fact that Kenny remains incarcerated and--if the system has its way--will die in prison means that justice still has not been served.

Lily Hughes, the CEDP's national director, spoke during the opening plenary, discussing the state of the death penalty today and explaining why its use has declined and the importance of our movement connecting to the broader fight around criminal justice.

In a session on "Two Cases of Injustice: Stop the Execution of Rodney Reed and Louis Castro Perez," both Sandra Reed, Rodney's mother, and Delia Perez Myers, the sister of Louis Castro Perez, spoke about the fight for their loved ones and their continued determination to stop the execution system.

It wasn't lost on anyone in the room that both cases are in their critical last legal stages. Delia Perez Myers described her anger over evidence that was only recently discovered because prosecutors had buried it. Meanwhile, Sandra said she and her family remained focused on the struggle for Rodney. "We have to keep fighting" Sandra said.

AFTER THE plenary sessions, there were workshops to take on issues such as "The Torture of Solitary," where presenter Randi Jones Hensley taped out markings on the floor to show the small space that prisoners are confined to when stuck in solitary confinement for up to 23 hours a day. "Just imagine what that's like--to be in that small space day after day after day. And many prisoners spend years of their lives there. It's an inhumane and unjust punishment."

Mark Clements, a former police torture victim from Chicago who spent 28 years unjustly incarcerated, also spoke at the workshop and brought home the deplorable conditions of today's prisons: "They treat you worse than a dog."

Student Blaine Anderson, who was attending the CEDP's convention for the first time. approached another presenter, journalist Liliana Segura, to say that "this is one of the best conferences I've ever been to, and I've attended many prison justice-type conferences." Anderson said she had never really thought about how family and loved ones are affected by the injustice system, and how moved she was listening to people whose lives have been forever altered.

That power probably came through most clearly when Terri Been, whose brother Jeff Wood is currently on Texas death row, also under the unjust "Law of Parties" rule, spoke from the audience. Choking back sobs and surrounded by her sons who took turns consoling her, Been talked about what it was like when Jeff came within hours of being executed in 2008:

I just couldn't do it, I just could not go in and watch them kill my brother--even though he wanted me there. And I just don't know what else I can do. I can't sleep, I'm a nervous wreck. They want to kill my brother, and I don't know how to protect him.

While the pain of family members like Terri Been was real and shared throughout the conference, so was the determination to fight.

LaKiza--the sister of Larry Jackson, who was killed over a year ago by an Austin police detective, who followed him and shot him in the back--spoke about her continued pursuit of justice. The cop, Charles Kleinert, was indicted for murder, but a judge threw out the indictment--that ruling is being appealed. "We are going to keep up the pressure because I am not about to give up," LaKiza said.

THE EVENING panel discussion was probably the most uplifting event of the conference. Facilitated by Sandy Joy, the audience heard from two exonerated death row prisoners who work with Witness to Innocence--as well as Kenneth Hartman, who is serving a life without the possibility of parole sentence. Hartman called in from prison to explain how his sentence and one that 50,000 other people endure is really just "the other death penalty, a lethal term of imprisonment."

You could hear a pin drop as Sabrina Butler, the first woman ever exonerated and freed from death row, told us what it was like to be convicted of killing her 9-month-old baby when she was just 18. "I was trying to help him," she said. "I was giving him CPR on the way to the hospital, but they said I killed him." She spent over six years on death row in Mississippi before winning her freedom. She implored us to keep up the fight against the racist injustice system.

DeWayne Brown, who goes by the nickname "Dough-B," spent 12 years wrongfully incarcerated, 10 of them on Texas' death row. He has been free since June of this year, and he talked about the difficulty in adjusting to life on the outside, but you would never know it by the easy way he addressed the audience.

He emphasized how desolate and isolating it is when you are on death row. "The quietist part of the day on Texas death row is when it's mail call. The radios go down, the talk stops, and men stand by their doors, hoping the guard stops and gives them a letter." He urged us to keep reaching out to those still locked up: "Let them know you are thinking about them, and they aren't forgotten."