Greater than the Cassius of old

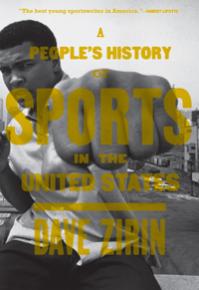

Muhammad Ali, who died last week at the age of 74, was a towering figure in the world of sports. But he should be remembered, as Nation sports columnist put it in an article for the Los Angeles Times, not as "a sanctified sports hero," but a "powerful, dangerous political force." In September 2008, SocialistWorker.org published an excerpt from one of Zirin's books, A People's History of Sports in the United States, in which he explained how Ali's impact on sports and American society continues to this day.

MUHAMMAD ALI'S identity was forged in the 1950s and 1960s, as the Black freedom struggle heated up and boiled over. He was born Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr. in Louisville, Kentucky, in 1942. His father, a frustrated artist, made his living as a house painter. His mother, like Jackie Robinson's mother, was a domestic worker. The Louisville of 1942 was a segregated horse-breeding community, where being Black meant being seen in service-oriented jobs and rarely heard.

But the young Clay could do two things that set him apart: he could box, and he could talk. His mouth was like that on other no fighter or athlete or any public Black figure anyone had ever heard. Joe Louis used to say, "My manager does my talking for me. I do my talking in the ring." Clay talked, inside the ring and out. The press called him the "Louisville Lip," "Cash the Brash," "Mighty Mouth" and "Gaseous Cassius." He used to say he talked so much because he admired the style of a pro wrestler named Gorgeous George. But in an unguarded moment, he once said, "Where do you think I'd be next week if I didn't know how to shout and holler and make the public take notice? I'd be poor, and I'd probably be down in my hometown, washing windows or running an elevator, and saying 'yassuh' and 'nawsuh,' and knowing my place."

Ali, of course, could back up the talk. His boxing skills won him the gold medal in the 1960 Olympics at age 18. When he returned from Rome--and this was the first step in his political arc--the young Clay held a press conference at the airport, his gold medal swinging from his neck, and said:

To make America the greatest is my goal

So I beat the Russian, and I beat the Pole

And for the USA won the Medal of Gold.

Italians said "You're greater than the Cassius of old."

Clay loved his gold medal. Fellow Olympian Wilma Rudolph remembered, "He slept with it, he went to the cafeteria with it. He never took it off." The week after returning home from the Olympics, Clay went to eat a cheeseburger with his medal swinging around his neck in a Louisville restaurant--and was denied service. As he later said, that medal found a home "at the bottom of the Ohio River."

The young Clay actively looked for political answers and began finding them when he heard Malcolm X speak at a meeting of the Nation of Islam. He heard Malcolm say, "You might see these Negroes who believe in nonviolence and mistake us for one of them, and put your hands on us, thinking that we are going to turn the other cheek--and we'll put you to death just like that." Malcolm X was an attractive figure. His impatience, his militancy, his rejection of nonviolence and his stony-eyed critiques of Democratic politicians and middle-of-the-road civil rights leaders gave him a following far beyond his organization.

As Malcolm X said in 1964,

You'll get freedom by letting your enemy know that you'll do anything to get your freedom; then you'll get it. It's the only way you'll get it. When you get that kind of attitude, they'll label you as a "crazy Negro," or they'll call you a "crazy nigger"--they don't say Negro. Or they'll call you an extremist or a subversive or seditious or a red or a radical. But when you stay radical long enough and get enough people to be like you, you'll get your freedom.

The young fighter and Malcolm X became both political allies and fast friends. Malcolm stayed with Clay as he trained for his fight against the "Big Ugly Bear," the champion Sonny Liston.

Before he had signed to fight Clay, Liston had been portrayed in the press as eight steps beyond evil. He had an arrest record that could fill a file cabinet and had been in the past employed by the mob as a strike-breaker and enforcer. Radical poet Amiri Baraka (then LeRoi Jones) called Liston "the big black Negro in every white man's hallway, waiting to do him in, deal him under for all the hurts white men, through their arbitrary order, have been able to inflict on the world."

Before Liston's championship fight when he won the title against Floyd Patterson, President Kennedy took the time to call Patterson and express that it would not be in "the Negroes' best interest" if Liston won. As one writer noted dryly, "The fight definitely was not in Patterson's best interest." Liston destroyed Patterson, setting the stage for his fight against Clay.

The writer James Baldwin was sent to cover Liston before the fight. He wrote, "[Liston] is far from stupid; is not, in fact, stupid at all. And while there is a great deal of violence in him, I sensed no cruelty at all. On the contrary, he reminded me of big, Black men I have know who acquired the reputation of being tough in order to conceal the fact that they weren't hard. Anyone who cared to could turn them into taffy."

But by this point, most of the press were paying far more attention to Clay, little of it positive. With Malcolm around, rumors flew that Clay was going to join the Nation of Islam, and the press hounded him, wanting to know. At one point, he said, "I might if you keep asking me."

While everyone was predicting an easy knockout for Liston, Malcolm said that Clay would win. He "is the finest Negro athlete I have ever known, the man who will mean more to his people than Jackie Robinson, because Robinson is the white man's hero." Malcolm also pointed out, "Not many people know the quality of mind he has in there. One forgets that though a clown never imitates a wise man, the wise man can imitate the clown." Although the verdict was out on whether he was wise or a clown, no one gave him a chance against Liston. But Clay--quicker, stronger and bolder than anyone knew--shocked the nation and beat Liston. He then shouted to the heavens, over a reporter's questions, "I'm king of the world!"

When Clay said he was the greatest, it wasn't far from the truth. The day after he beat Liston, he announced publicly that he was a member of the Nation of Islam, causing a firestorm. The fact was that the heavyweight champion of the world was joining the organization of Malcolm X. The Olympic gold medalist had linked arms with a group that called white people "devils" and stood unapologetically for self-defense and racial separation. Not surprisingly, the power brokers of the conservative, mobbed-up, corrupt fight world lost their minds. Jimmy Cannon, the most famous sportswriter in America, apparently forgetting the entire career of Jack Johnson, wrote that this was the first time that boxing had ever "been turned into an instrument of mass hate...Clay is using it as a weapon of wickedness."

Clay was attacked not only by Cannon and his ilk but also by the respectable wing of the civil rights movement. "Cassius may not know it, but he is now an honorary member of the White Citizens' Councils," said Roy Wilkins. Clay's response at this point was very defensive. He repeatedly said that his wasn't a political stand, but purely a religious conversion. His defense reflected the conservative perspective of the Nation of Islam: "I'm not going to get killed trying to force myself on people who don't want me...Integration is wrong. The white people don't want integration, and the Muslims don't believe in it. So what's wrong with the Muslims?" At another point, he said, "I have never been to jail. I have never been in court. I don't join any integration marches...I don't carry signs."

But much like Malcolm X, who at the time was engineering a political break from the Nation, Clay--much to the anger of Elijah Muhammad--found it impossible to explain his religious worldview without speaking to the mass Black freedom struggle exploding outside the boxing ring. He was his own worst enemy--claiming that his was a religious transformation and had nothing to do with politics, but then, in the next breath, saying, "I ain't no Christian. I can't be when I see all the colored people fighting for forced integration get blowed up. They get hit by stones and chewed by dogs, and they blow up a Negro church." Unrepentantly, Clay said, "People are always telling me what a good example I could be if I just wasn't a Muslim. I've heard it over and over, how come I couldn't be like Joe Louis and Sugar Ray. Well, they've gone now, and the Black man's condition is just the same, ain't it? We're still catching hell."

If the establishment press was outraged, the new generation of activists was electrified. "I remember when Ali joined the Nation," remembered civil rights leader Julian Bond. "The act of joining was not something many of us particularly liked. But the notion that he would do it, that he'd jump out there, join this group that was so despised by mainstream America and be proud of it, sent a little thrill through you...He was able to tell white folks for us to go to hell; that I'm going to do it my way."

For a time, he was known as Cassius X, but Elijah Muhammad gave Clay the name Muhammad Ali--a tremendous honor and a way to ensure that Ali would side with Elijah Muhammad in his split from Malcolm X. Ali proceeded to commit what he would later describe as his greatest mistake--turning his back on Malcolm. But the internal politics of the Nation were not what the powers that be and the media noticed. To them, the Islamic name change--something that had never occurred before in sports--was a sharp slap in the face.

Almost overnight, whether an individual called the champ Ali or Clay indicated where that person stood on civil rights, Black power and eventually the war in Vietnam. The New York Times insisted on calling him Clay as editorial policy for years thereafter.

This all took place against the backdrop of a Black freedom struggle rolling from the South to the North. During the summer of 1964, there were a thousand arrests of civil rights activists, 30 buildings bombed and 36 churches burned by the Ku Klux Klan and their sympathizers. In 1964, the first of the urban uprisings and riots in the northern ghettoes took place in Harlem. The politics of Black Power was starting to emerge, and Muhammad Ali became the critical symbol in this transformation. As news anchor Bryant Gumbel said, "One of the reasons the civil rights movement went forward was that Black people were able to overcome their fear. And I honestly believe that for many Black Americans, that came from watching Muhammad Ali. He simply refused to be afraid. And being that way, he gave other people courage."

A concrete sign of Ali's early influence was seen in 1965 when Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) volunteers in Lowndes County, Ala., launched an independent political party. Their new group was the first to use the symbol of a black panther. Their bumper stickers and T-shirts were of a black silhouette of a panther, and their slogan was straight from the champ: "We Are the Greatest." It's this broader context that allows us to understand why Ali's post-name-change fights--like the Louis-Schmeling fight years before--became incredible political dramas of the Black revolution versus the people who opposed it. Floyd Patterson, who wrapped himself tightly in the American flag, challenged Ali and said, "This fight is a crusade to reclaim the title from the Black Muslims. As a Catholic, I am fighting Clay as a patriotic duty. I am going to return the crown to America."

In the fight itself, Ali brutalized Patterson for the entire 12 rounds, dragging it out and yelling, "Come on America! Come on white America!" Future Black Panther Party leader Eldridge Cleaver wrote in his 1968 autobiography Soul on Ice, "If the Bay of Pigs can be seen as a straight right hand to the psychological jaw of white America, then [Ali/Patterson] was a perfect left hook to the gut."

© 2008 by Dave Zirin. This piece originally appears in Dave Zirin's A People's History of Sports in the United States (The New Press, 2008). Published with the

permission of The New Press and available at good book stores everywhere.