The revolutionary legacy of the Black Panthers

What can today's left learn from the Black Panther Party, formed 50 years ago in California? and look at the Panthers' history and legacy.

THE BLACK Panther Party for Self-Defense emerged in the late 1960s at a turning point in the Black movement, as the focus of the struggle turned from the civil rights movement in the South to Black Power in the North--and its goals from reform to revolution.

Founded 50 years ago in October, the Panthers became the most prominent icon of Black Power, known the country and the world over for their militant commitment to self-defense, their self-sacrificing dedication to the cause of liberation and their revolutionary politics.

Within a few short years, the party had an active membership numbering in the thousands, and a following that was many times larger. The weekly Black Panther newspaper had a circulation of a quarter-million copies at its high point, according to one estimate. By May 1969, the Chicago chapter alone was selling 8,000 copies of the paper each week--soon to increase to 15,000 weekly.

In 1970, one opinion poll found that 25 percent of African Americans had great respect for the Panthers, including 43 percent of Blacks under 21--and five in every six African Americans at least agreed with the Panthers that Black people needed to unite to defend themselves.

The fall of the Panthers came just as quickly, as the organization endured the full brunt of state repression and violence, and became embroiled in political debates and conflicts common to many revolutionary organizations of the time.

Since then, many books and movies have come out that attempt to define the Panthers' legacy. Some at least have the explicit aim of smearing the Panthers as bent on violence and responsible for their own destruction.

But the left today--especially in light of the rise of the Black Lives Matter struggle--needs to understand and champion the legacy of the Panthers. All the questions that the Panthers faced--not only the conditions of racist police violence, poverty and oppression, but the question of how to organize to challenge these conditions--are still with us.

Whatever mistakes were made and opportunities missed, the Black Panther Party (the words "for Self-Defense" were later dropped) won a mass audience for revolutionary socialist politics on a scale unrivaled in the U.S. since the 1930s. The Panthers proved that a radical challenge to the system could be not only popular, but gain wide support in a society that we are told can never have a revolution.

THE PANTHERS were founded in Oakland, California, in October 1966 by Huey Newton and Bobby Seale.

The two met at Merritt College in Oakland, where they participated in Black nationalist formations such as the Afro-American Association and the Revolutionary Action Movement (RAM). At Merritt, Newton and Seale led the RAM-sponsored Soul Students Advisory Council (SSAC), which organized a successful struggle to get Black studies added to the curriculum.

Following up on this victory, Newton proposed that the SSAC should take up police violence. In the aftermath of the Watts rebellion in Los Angeles the summer before, Oakland police had begun carrying shotguns, and instances of police brutality were on the rise.

When the SSAC decided against their plan for members to "patrol the police"--including carrying weapons, which was legal in California at the time--Newton and Seale decided to form the Panthers.

The Panthers' focus on self-defense wasn't necessarily a new idea--the Deacons of Defense had come together mainly in the South to protect the civil rights movement from attacks by police and vigilantes. The group's name--the Black Panthers, taken from the symbol of the Loundes County Freedom Organization in Alabama--was already being used as well.

In LA, patrols of the police were carried out after the Watts rebellion by the Community Alert Patrol, whose observers followed police cars through Black neighborhoods.

There was one big difference with Newton and Seale's proposal, though: The Panthers were armed.

A typical patrol would involve three or four Panther members following police cars until officers pulled someone over. The Panthers, displaying their guns openly in accordance with the law, would jump out of their car and perform a "cop watch," monitoring the action so the police didn't use undue force. The Panthers carried around law books to let people know their rights--and to show cops the law if officers questioned their right to bear arms.

The spark immediately started a fire. The Panthers won respect among residents of the Bay Area for confronting racist police violence.

Eldridge Cleaver, soon to become a co-leader along with Newton and Seale, described his reaction when he first encountered Panther members providing security at an event where Malcolm X's widow Betty Shabazz was to speak: "I spun round in my seat and saw the most beautiful sight I had ever seen: four Black men wearing black berets, powder blue shirts, black leather jackets, black shoes--and each with a gun."

PATROLLING THE police was the lightning rod for the Panthers, but from the beginning, the organization was about more than self-defense against racist cops. Newton, Seale and Cleaver were all revolutionaries, influenced by various radical and socialist traditions.

The Panthers formed as the civil rights movement faced an impasse. Mass mobilization and direct action in the Jim Crow South had forced Congress to pass legislation that legally ended segregation and disenfranchisement.

But this raised new questions about guaranteeing the gains in reality and confronting other forms of inequality and oppression. Civil rights activists grappled with the fact that their sit-ins at lunch counters or on buses could directly confront segregation, but it was hard to figure out how to nonviolently disrupt Black unemployment, substandard housing, poor medical care or police brutality.

The challenges were crystallized when Martin Luther King Jr. attempted to open a campaign in the North against de facto segregation and economic inequality. It met with violence every bit as brutal as in the South--but also hostility from northern Democratic Party leaders who might have supported the Southern civil rights struggle in words, but wanted nothing to do with a confrontation in their backyard.

The focus of the movement shifted from civil rights to "Black Power"--a phrase coined by Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) leader Stokely Carmichael (later known as Kwame Ture) on a 1966 march in Greenwood, Mississippi.

That coincided, in turn, with a string of rebellions in major U.S. cities, starting with Watts in 1965 and continuing for the next several years. These uprisings, involving both poor and working-class Blacks, were a bitter reaction to continuing poverty and lack of political power--and they were typically sparked off by an incident of police abuse or murder.

If Carmichael's slogan of Black Power spoke to the questions that this shift in the struggle raised, the Panthers pointed to an answer beyond their patrols of police with the party's Ten-Point Platform and Program, published in the second issue of The Black Panther newspaper, dated March 16, 1967:

What We Want Now!

1. We want freedom. We want power to determine the destiny of our Black Community.

2. We want full employment for our people.

3. We want an end to the robbery by the white men of our Black Community. [Later changed to "We want an end to the robbery by the capitalists of our Black and oppressed communities.")

4. We want decent housing, fit for shelter of human beings.

5. We want education for our people that exposes the true nature of this decadent American society. We want education that teaches us our true history and our role in the present day society.

6. We want all Black men to be exempt from military service.

7. We want an immediate end to POLICE BRUTALITY and MURDER of Black people.

8. We want freedom for all Black men held in federal, state, county and city prisons and jails.

9. We want all Black people when brought to trial to be tried in court by a jury of their peer group or people from their Black Communities, as defined by the Constitution of the United States.

10. We want land, bread, housing, education, clothing, justice and peace.

From the first point, the platform makes the connection between the civil rights movement's call for freedom and the practical implications of this demand in Northern cities where African Americans were already free on paper, but continued to suffer oppression in practice. The Panthers declared that "freedom" must be connected to having the "power to determine the destiny of our Black Community."

Other planks of the Ten-Point Platform and Program put class questions--"full employment," "an end to the robbery," "decent housing" and "education for our people"--at the center of the freedom struggle.

The Panthers' statement of program also implied different methods of fighting for their demands. The strategy of the civil rights movement was to pressure the federal government for policies and legislation that could be used against the rulers of the Jim Crow South. The Panthers, on the other hand, rejected the power of the U.S. state to draft African Americans into the military, subject them to repression by police or imprison them in its jails.

MEANWHILE, THE Panthers' willingness to confront police won respect and support in the Bay Area, and very soon, across the country.

In January 1967, after police in Richmond, north of Oakland, murdered an unarmed Black man, Denzil Dowell, the Panthers were called in by residents. The group led an armed march to the police station to demand the real details about the case. The Panthers put enough pressure on the district attorney that he prosecuted the cop. The case ended in acquittal, but the Panthers showed they could get action.

Responding to the Panthers' armed protests, the California legislature took up a bill to limit the carrying of loaded weapons in public--it was the start of the modern gun control movement, aimed at radical activists who armed themselves in self-defense against police violence.

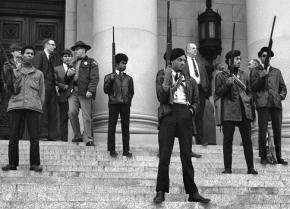

The Panthers responded with an electrifying demonstration in the state capital in Sacramento. A delegation of 24 men and six women, carrying loaded pistols and shotguns, marched into the Capitol building, past Gov. Ronald Reagan, and onto the floor of the state Senate, where Bobby Seale read a statement against "legislation aimed at keeping Black people disarmed and powerless."

At this point, the Panthers had only about 75 members, all in the Oakland area. But press coverage of the march into the legislature--including images of members brandishing weapons--got the organization further national attention. The Mulford Act was passed quickly by the state legislature, but Newton and Seale were undaunted, seeing the event as one that would galvanize support for the organization.

On October 28, 1967, Huey Newton was stopped by police while driving home from a demonstration. In a shootout that followed, an officer was killed, and Newton was wounded.

Newton was arrested and charged with murder, but his lawyer proved that police started the shootout, and the charge was reduced to manslaughter. Newton was eventually sentenced to a two- to 15-year prison term--he served three years and was released in 1970.

Thus, a co-founder of the organization spent the most important years of the Panthers' existence behind bars. But the "Free Huey" campaign drew tremendous attention to the party, winning it support from the wider left, including thousands of largely white college students who mobilized solidarity on campuses throughout the country.

In February 1968, the Panthers held a mass rally in Oakland of some 6,000 people. With Seale also imprisoned at the time, the Panthers' Minister of Information Eldridge Cleaver spoke, sharing the stage with well-known SNCC leaders Stokely Carmichael, James Foreman and H. Rap Brown. With no police in sight, the rally had the feeling of a liberated zone.

With Newton in prison and Seale also frequently incarcerated, Cleaver became the party's dominant figure in the public eye. Later in 1968, the Panthers joined forces with the Peace and Freedom Party (PFP) to run a left-wing electoral campaign, with Cleaver as the presidential nominee.

Cleaver electrified audiences during his speeches on campuses as the student movement radicalized in the face of events like the police riot in Chicago at the 1968 Democratic convention. In the end, he won 200,000 votes for president.

THE ALLIANCE with the PFP underlined the Panthers' willingness to work with left organizations whose members and supporters were mostly white. This set the Panthers apart from many Black nationalist organizations, but the Panthers adamantly defended such alliances.

Responding to denunciations from separatist groups, Huey Newton used a prison interview in August 1968 to sharply criticize cultural nationalists, who he called "pork chop nationalists."

Newton defined the revolutionary nationalism of the Panthers as explicitly socialist:

There are two kinds of nationalism, revolutionary nationalism and reactionary nationalism. Revolutionary nationalism is first dependent upon a people's revolution with the end goal being the people in power. Therefore, to be a revolutionary nationalist, you would by necessity have to be a socialist. If you are a reactionary nationalist, you are not a socialist, and your end goal is the oppression of the people.

The Panthers' vision of the struggle was more embracing than many other Black radicals of the time. In 1970, Newton gave a speech endorsing women's liberation and gay liberation, a radical departure in a left where conservative and even backward ideas festered because of the predominance of Stalinism, particularly in its Maoist variety inherited from the Chinese Revolution.

At the same time, though, the Panthers' politics fluctuated and shifted--as was probably inevitable in an organization with such a meteoric rise. Thus, Cleaver could talk about a coming second Civil War "with thousands of white John Browns fighting on the side of Blacks" in one October interview, while at the same time naming the anarchistic Yippies, with their focus on theatrical stunts, as "our allies in this human cause."

Moreover, both Cleaver and Newton were drawn to the idea--inherited from Maoism and common on the U.S. left in this era--that revolutionary change would be made through armed struggle. In the same interview where Newton committed the Panthers to socialism, he stressed the duty of revolutionaries to take part in such a struggle. "The guerrilla is the military commander and the political theoretician, all in one," he said.

Meanwhile, the Panthers showed another facet, especially in the poor Black neighborhoods that were the organization's base, with its commitment to "serving the community."

Operating in areas where social services were inaccessible to nonexistent, the Panthers established their famous free breakfast program for children, along with free health clinics and clothing distribution, liberation schools emphasizing African American history, an elderly escort and bus service, and free plumbing and maintenance services.

This, too, reflected the influence of Maoism--with its vision of a revolutionary cadre who would "serve the people." Seale explained that the Panthers understood their social programs not as an accommodation to the existing system, but part of a revolutionary project:

Some people are going to call these programs reformist, but we're revolutionaries, and what they call reformist programs is one thing when the capitalists put it up, and it's another thing when the revolutionary camp puts it up. Revolutionaries must always go forth to answer the momentary desires and needs of the people, the poor and the oppressed people, while waging the revolutionary struggle.

THE EXPLOSIVE growth of the Panthers began with the Free Huey campaign at the end of 1967. In the first half of the next year, the organization established 12 new chapters and more than 1,000 people joined. By early 1969, the Panthers had as many as 5,000 members.

But the violent repression that landed Newton behind bars continued to take a toll.

Local police routinely raided Panther offices, supposedly searching for illegal weapons--and because they came in shooting, many one-sided battles ensued. In the two-year span of 1968-69, more than 35 Panthers were killed and at least twice as many were wounded by police.

Two days after the assassination of Martin Luther King in 1968, police opened fire unprovoked in a confrontation with Panthers in Oakland. Cleaver was wounded, and Bobby Hutton, Newton and Seale's first recruit back in 1966, was killed. Cleaver spent two months in prison.

FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover directed the full brunt of the COINTELPRO program--launched in the mid-1950s to "disrupt and destabilize," "cripple," "destroy" and otherwise "neutralize" radical organizations--against the Panthers.

The targeting of Panthers led to 348 felony arrests of Panthers in 1969 alone. FBI and local police coordinated efforts, often conducting joint raids--or just plain drive-by shootings--on Panther headquarters. Later revelations showed the FBI gave local police "shoot to kill" orders.

In April 1969, 21 Panther members in New York were arrested on conspiracy charges for allegedly plotting to blow up public buildings. The prosecution ultimately collapsed, and all defendants were acquitted, but not until May 1971.

Another COINTELPRO tactic was to infiltrate the Panther organization--police agents then helped set up raids, frame the organization's leaders and provoke confrontations. The FBI also forged letters to try to sow hostility. One operation tried to encourage David Hilliard, a prominent member of the group, to kill Huey Newton.

All the while, the death toll continued to rise. In January 1969, two Panther leaders in LA were murdered by members of a cultural nationalist organization who are now believed to be FBI infiltrators.

Later in the year, Fred Hampton--leader of the Chicago chapter of the Panthers and a deputy minister of the party nationwide--was murdered along with Mark Clark as they slept. After an informant set up the raid, county sheriff's deputies, backed up by Chicago police and FBI agents, stormed their home with guns blazing. Not a single officer ever stood trial for this cold-blooded murder.

Repression on this barbaric scale continued for the rest of the Panthers' short life as a viable organization. But violence alone didn't crush the organization. Newton was still behind bars and Cleaver fled the country rather than face more prison time, but the Panther leaders, inside and outside prison, responded to the state's onslaught.

In early 1969, party Chairman Seale and David Hilliard, its chief of staff, led an attempt to expel police infiltrators and those who used the organization as a front for criminal activities or were interested solely in confrontations with police.

The reorientation included a deeper emphasis on political education. Party leaders from California traveled regularly to the branches, and leaders of new chapters were expected to come to Oakland for six weeks of training. As Hilliard wrote in his autobiography, the weekly Black Panther newspaper--which never stopped publishing, even at the height of the repression--became:

synonymous with our invincibility, and its publication is one of our top priorities. No more once-every-two-or-three-week issues like we used to publish with Eldridge. Now the paper will appear like clockwork, every Thursday, our lifeline to the chapters and community and a visible sign of our defiance of the pigs.

DESCRIPTIONS LIKE these help to dispel the false depiction of the Panthers, popular in many mainstream histories, as primarily interested in violent confrontations with police, and using revolutionary rhetoric only to justify them. The politics of the Panthers were highly developed and deserve close study--more study than an introductory article can summarize.

The Panthers faced the same questions as other left organizations of the era, and how they answered them was influenced by the dominant revolutionary politics of the U.S. left at the time: Maoism and the associated ideas of Third World guerrilla struggles for liberation.

As Ahmed Shawki wrote in his book Black Liberation and Socialism, Maoism was:

prevalent among radicals because it had a number of characteristics that made it attractive to a younger generation...It offered a general identification with Third World liberation movements, like the one in Vietnam, and...it fit with the lack of confidence in working-class forces as the catalyst for change.

This particular variant of "socialism from above" shaped the Panthers' basic conceptions of the role and form of revolutionary organization. Shawki writes that this is particularly important in understanding the Panthers' orientation on "the boys off the block"--poor and often unemployed Black youth:

The emphasis on organizing the most dispossessed and marginalized--analogous to the peasantry from which Third World guerillas drew their support--made the Panther organization unstable...This instability made the party more easily infiltrated. The emphasis, more with members than others, on the "gun" allowed the U.S. government to isolate and "outlaw" the BPP.

The Panthers probably transcended the weaknesses of Maoism more than other revolutionary organizations. For example, women played a leading role in the Panthers, though the party contended throughout with instances of sexism and violence against women.

But the Panthers' organizational forms throughout its existence were top-down, rather than bottom-up. Panther leaders were given military-political ranks--like chairman for Seale, minister of defense for Newton, chief of staff for Hilliard and so on. The Panthers' central committee was selected by the top leadership, not elected.

This doesn't mean there was no room for debate and disagreement within the organization. Various Panther chapters took initiatives and developed their own priorities--for example, the Chicago chapter led by Fred Hampton stressed building alliances, in the form of a "Rainbow Coalition" that included the Young Lords based in Puerto Rican neighborhoods and the Young Patriots Organization comprised of poor whites.

As long as the Panthers were moving with the tide of radicalization and immediate responses--like the showdown in the state Capitol in Sacramento--kept the forward momentum going, the party thrived. But when the Panthers faced more difficult questions, the lack of a democratic structure that could represent the experience of the whole organization to develop a way forward became a significant problem.

AS THE Panthers were on the rise, another strand of the Black Power movement pointed toward different political and organizational conclusions to the Panthers' orientation on the so-called "boys off the block."

First in Detroit and then in other cities, the League of Revolutionary Black Workers put the spotlight on the economic power of Black workers specifically and the working class in general.

The League formed as an extension of the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement (DRUM), an organization of Black autoworkers at a Chrysler plant in Detroit that confronted both the tyranny of the auto bosses and the racism of the bureaucratized United Auto Workers union. DRUM's militant spirit won a loyal following, including among a section of white workers.

The working-class focus of the League influenced the formation of the Black Panther Caucus at the giant General Motors factory in Fremont, California, south of Oakland. With Panthers organizing around workplace issues a short distance from party headquarters, the Black Panther newspaper started carrying more regular coverage of labor struggles, at Fremont and beyond.

In April 1969, John Watson of the League of Revolutionary Black Workers came to Oakland to participate with Panther leaders in a conference that the Panther newspaper hoped would be a "historic breakthrough we've been working toward: a Black community-worker alliance."

The conference showed how an orientation on Black working-class struggles fit naturally with the class politics that distinguished the Panthers from their origin. But this tendency within the Panthers never became central--at least in part because it conflicted with other priorities for the party.

The League's emphasis on workplace struggle offered a way of involving broader layers of working-class people in radical politics, based on their common interests as workers. That potential contrasted with the organizing model of the Panthers, with its core of revolutionaries who saw themselves as acting on behalf of the wider Black community, whether by patrolling the police or providing services or some other function.

The all-consuming commitment to the struggle of Panther members is undisputed and an inspiration. But the political priorities and conceptions of the party made it difficult, if not impossible, to participate on anything less than a full-time basis. This further contributed to the dynamic, inherited from Maoism, that separated revolutionaries from the masses they sought to serve.

THERE IS much more to say about the politics of the Panthers and its organizational history. Fortunately, many sympathetic books and studies are available--for example, Donna Murch's Living for the City: Migration, Education and the Rise of the Black Panther Party in Oakland--to learn more.

What's most amazing, in some ways, is how many revolutionary experiences and lessons are compressed into the Panthers' brief history. By 1972 at least, the Panthers were suffering an organizational crisis--caused directly by savage state repression, but worsened by political disorientation and disarray.

When the central core of revolutionaries whose vision defined the Panthers and held the organization together began to splinter, the party as a whole did as well.

Operating in exile, Eldridge Cleaver emphasized armed struggle more and more. Bobby Seale moved in the opposite direction--by 1972, he stepped back from the Panthers in order to run for mayor of Oakland, while the Panthers endorsed the campaign of U.S. Rep. Shirley Chisholm for the Democratic Party presidential nomination.

Both before and after his release from prison in 1970, Huey Newton made vital but shifting contributions--he would later declare the expulsion of Cleaver, Seale and Hilliard. Though the Panthers continued to exist in name, the organization had effectively collapsed by 1973.

But, of course, the legacy of the Black Panther Party can't be reduced to this period of its decline. It remains a towering example to today's left as the most significant openly revolutionary organization in the U.S. in the era after the Second World War. Socialists and radicals need to stand on its shoulders to see further.

Even in the face of repression, the Panthers experienced profound successes, from the self-defense of Black communities to the mass following it attracted and shaped. But it's also important to see how the Panthers thrived as part of a larger radicalizing left, including the antiwar struggle, women's movement, Native American struggles, the gay liberation movement and the rank-and-file uprising in U.S. unions.

The same questions that the Panthers confronted are with us today, along with the same urgency to take action to change the world. Remembering the Panthers 50 years later can help us find the way down that road.

Thanks to Lee Sustar for sharing with us his research on the Black Panthers and insights on the political questions taken up here.