What if workers ran society?

If capitalism is a system that concentrates power in the hands of a small minority, the alternative of socialism is exactly the opposite, writes .

CAPITALISM IS, among other things, a system of "experts."

In the halls of government, politicians and policy makers decide for us when to go to war and when to fund social services. In courtrooms, judges decide what constitutes a crime and a criminal, based on testimony and argument from police and lawyers.

In workplaces, efficiency experts decide the best way to organize the desks or the machines or the hospital beds--and the owners and capitalists decide what should be produced and how much of it, based on what their financial experts tell them.

The majority of people--the non-"experts" who work in the workplaces and are prosecuted by the laws--also make important decisions every day.

A worker with asthma decides whether to risk getting fired in order to stay home to take care of their health. Another decides whether it's worth drawing attention to himself by filing a safety complaint or just working around the problem. An undocumented immigrant decides to look the other way while her boss steals her wages, for fear of being detained and deported.

On any given day, millions of workers make important and sometimes life-changing decisions. But they make them under conditions they have no control over.

They make them under conditions created by the "experts" in society. And while workers base their decisions on how to best to survive under these conditions, the experts have a higher purpose--profit.

THE DECISIONS these so-called experts make are in the interest of capitalism and ensuring an unequal situation--in which the majority work so that a minority can reap the profits, which by its definition means that the people who do the work never see the full fruits of their labor.

If they live in the U.S., workers can vote for candidates and sometimes on ballot initiatives every few years. They can call their representatives and lobby on an issue. But their input is far removed from the actual decision-making process in Washington or their state and city governments.

And workers are even farther away from the decision-making where they work, even though that's where they spend the bulk of their waking hours.

This, however, doesn't mean that workers couldn't make all the decisions that are out of their hands under capitalism--that are made by experts or an elite.

If you don't believe that, ask a nurse. Understaffing and long hours are hallmarks of health care in the U.S., creating dangerous situations for patients and nurses who care for them.

Talk to most nurses, and they will tell you what resources they need to make sure that patients get the care they need. They can also tell you where to cut the waste that for-profit health care generates, and how some of the work rules and all of the supervisors get in the way of care.

While we're on the subject, ask someone at a health insurance company what their job would look like if the health care system prioritized care for everyone. If they were honest, they would tell you that the company they work for should be eliminated.

Under capitalism, rules are imposed primarily to increase productivity and profit, at the expense of workers' well-being. Discipline is imposed on workers in various ways--through supervisors enforcing company procedures, through co-workers being pitted against one another, or through the threat of unemployment since there is always a reserve of workers without jobs to take our place.

Alongside these forms of coercion in the workplace, state institutions impose further discipline on workers. That's where the cops and prisons come in.

WHEN REVOLUTIONARY socialists talk about "socialism from below" and a workers' government, we mean workers making decisions about the way that all of society is organized--from what happens at their workplaces to how the resources of society should be used.

The iron wall between what are considered "political" and "economic" questions would have to fall away.

Today, "politics" appears to float above the things that happen every day at work. But when you scratch beneath the surface, this isn't the situation at all. With every decision they make, our elected officials fundamentally work in the interests of capitalism, even while they are vulnerable to public pressure and protest.

And while state institutions under capitalism like the police and the courts are perfect for disciplining workers and maintaining inequality and profit, they are completely useless for a system that prioritizes providing for human need above all else.

During the process of struggle, when workers come into conflict with the status quo, they arrive at new conclusions--about themselves and the people they work with, as well as their rulers. During sustained revolutionary struggle, ideas can change dramatically, including about whether workers themselves are more capable of running society.

Karl Marx pioneered a version of socialism that could only be achieved by the working class itself. His phrase "the emancipation of the working classes must be conquered by the working classes themselves" became a watchword of the socialist movement.

Marx identified the source of workers' power in their position of creating all wealth in society and their resulting power to shut it down--which they are able to do only through their collective strength.

So if workers' power is in their collective strength as a class, a workers' government would be based on where their power lies--the workplace.

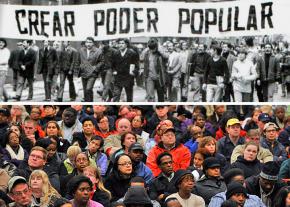

CURRENTLY, WORKERS wield no power and make no decisions at work, and the only votes they have are far removed from their everyday lives. But during times of struggle historically, workers have formed their own democratic structures to build the greatest unity and make day-to-day decisions--as in the case of workers' committees during a strike.

In times of revolutionary upheaval, these basic forms of workers' democracy combine to become councils, with elected leadership. These examples show how a worker-run democracy is not only possible, but can challenge the existing state. They give us an important glimpse into what a society would look like with workers in the driver's seat.

There are many examples through history of workers' councils that deserve to be read about individually: The Paris Commune of 1871, the Russian revolutions of 1905 and 1917, the Italian factory movement of 1919-20, Germany's revolutionary years from 1918 to 1923, the Spanish Revolution of 1936, Hungary in 1956, Portugal in 1974-75, Iran in 1979, Poland in 1980-81 and on and on.

Forms of workers' democracy arise during conditions of extreme crisis, when it seemed like the old order wouldn't be able to function in the same way as before.

For example, in Chile, the workers' councils, or cordones, emerged in opposition to a "bosses' strike" against the democratically elected government of socialist Salvador Allende--but they were largely a product of the class struggle that opposed the corrupt Frei regime before it.

When truck owners and factory bosses attempted to close down production in October 1972, the cordones responded immediately, while Allende was conciliatory, calling for order to be restored. As socialist author Mike Gonzalez wrote:

Trucks were forcibly taken and put back on the road, factories were occupied and kept at work, distribution was organized directly and shops reopened by local distribution committees--the Communal Commands--while medical personnel on the left kept the hospitals open. The so-called leadership of the workers' movement was left behind by this qualitative leap in the level and nature of workers' self-organization.

When the bosses' strike was defeated, it was clear that it was the Chilean working class that had inflicted that defeat.

Workers' confidence grew after these confrontations, and also exposed the weakness of the Allende government to defend itself, much less meet workers' demands.

DURING REVOLUTIONARY situations, the old structures and mechanisms prove to be inadequate for the kind of democracy that workers need to run society themselves.

In the process, workers come to see that another form of organization has to be created.

The Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky wrote about his experience with the workers' councils, known by the Russian word "soviets," during the 1905 revolution in Russia:

The Soviet came into being as a response to an objective need--a need born of the course of events. It was an organization which was authoritative and yet had no traditions; which could immediately involve a scattered mass of hundreds of thousands of people while having virtually no organizational machinery; which united the revolutionary currents within the proletariat; which was capable of initiative and spontaneous self control--and most important of all, which could be brought out from underground within 24 hours.

The Petersburg soviet, which formed out of a strike wave over economic demands, but also calls for greater political freedoms, was made up of delegates from striking factories. While it lasted only 50 days in 1905, it would be an important testing ground for the new workers' organizations that sprung up 12 years later.

As Trotsky wrote in his book 1905:

The soviet organized the working masses, directed the political strikes and demonstrations, armed the workers and protected the population against pogroms. Similar work was also done by other revolutionary organizations before the soviet came into existence, concurrently with it, and after it. Yet this did not endow them with the influence that was concentrated in the hands of the soviet.

The secret of this influence lay in the fact that the soviet grew as the natural organ of the proletariat in its immediate struggle for power as determined by the actual course of events. The name of 'workers' government,' which the workers themselves on the one hand, and the reactionary press on the other, gave to the soviet was an expression of the fact that the soviet really was a workers' government in embryo.

During the Russian Revolution of 1917, workers' councils once again formed the backbone of workers' organization. In June 1917, there were hundreds of soviets across Russia. After months of struggle, the workers' councils were eventually able to prevail over the old state structures that initially existed alongside it.

THE WORKING class faces a powerful and well-organized enemy--the ruling class with all its state institutions and ideology on its side. Workers will need their own centralized and democratic structures in order to make decisions and carry them out against such a powerful opponent.

During that process, workers--the real experts--develop their own organizing that help form the basis for future society, where the priority is fulfilling human need and everything else. This means not just the bare minimum, but the freedoms denied us in this society, like the time to debate and make decisions.

The American socialist John Reed described it this way in his Ten Days That Shook the World about the Russian Revolution:

In the new Russia every man and woman could vote; there were working-class newspapers, saying new and startling things; there were the soviets; and there were the unions...

At the front the soldiers fought out their fight with the officers, and learned self-government through their committees. In the factories those unique Russian organizations, the Factory-Shop Committees, gained experience and strength and a realization of their historical mission by combat with the old order. All Russia was learning to read, and reading--politics, economics, history--because the people wanted to know.

In every city, in most towns, along the front, each political faction had its newspaper–sometimes several. Hundreds of thousands of pamphlets were distributed by thousands of organizations, and poured into the armies, the villages, the factories, the streets.

The thirst for education, so long thwarted, burst with the revolution into a frenzy of expression. From Smolny Institute alone, the first six months, went out every day tons, carloads, trainloads of literature, saturating the land. Russia absorbed reading matter like hot sand drinks water, insatiable.