The debate about how much to cut

Both mainstream parties are devoted champions of the politics of austerity.

THE U.S. political and media establishment love to portray Republicans and Democrats as bitter enemies, constantly at war over every issue.

This picture helps the politicians themselves, by giving them a reason to rally their base supporters. And the media get to fill acres of newsprint and hours of airtime with analysis and speculation about the horse race between the parties, without ever considering ideas from outside the mainstream.

But the great unspoken truth about the U.S. political system is this: The differences between Republicans and Democrats, while real, are dwarfed by their much larger areas of agreement on one issue after another.

The unveiling of the Obama administration's budget proposal for next year provided another example of this truth. Once you look past the war of words over the budget, you realize that the two parties differ only about details--and that both are committed to an austerity agenda that puts the interests of Corporate America and Wall Street ahead of working people.

THE MEDIA conventional wisdom about the budget at least recognized that the Obama proposal was designed primarily for campaign propaganda purposes, and didn't stand a chance of passing a Republican Congress.

But it was still generally portrayed as a "progressive" alternative to the Republicans. According to the Guardian's account, for example, "Barack Obama set out the battles lines over the economy in this year's presidential election by proposing a budget that favors stimulus spending over austerity, and commits to the increasingly popular demand to raise taxes on the rich."

Not exactly.

It would be more accurate to say that Obama proposed a budget that favors austerity over even more drastic austerity--and that commits to talking about raising taxes on the rich, while not talking about how he retreated from doing precisely this during his first three years in office.

Jeffrey Sachs, the one-time champion of neoliberalism and now one of its harshest establishment critics, put the "budget battle" in perspective when he compared Obama's proposal with that of Rep. Paul Ryan, the Republicans' hardline spokesperson on the budget. As Sachs wrote in the Financial Times, Obama's plan would:

cut total primary (non-interest) federal spending from about 22.6 to 19.3 percent of gross domestic product from 2011 to 2020, while revenues would rise from recession lows of about 15.4 percent of GDP in 2011 to some 19.7 percent by 2020. Compare that with Republican congressman Paul Ryan's budget a year ago. Mr. Ryan's budget aimed for about 17 percent of GDP in primary outlays by 2020, with revenues at about 18 percent of GDP.

The difference is modest, but the important fact is this. Both sides are committed to significant cuts in government programs relative to GDP. These cuts will be especially [harsh] in the discretionary programs for education; environmental protection; child nutrition; job re-training; transition to low-carbon energy; and infrastructure.

In other words, the debate in Washington isn't about whether or not to cut, but whether to amputate at the knee or the hip.

If that statement seems extreme, consider the raw numbers. The Obama budget proposal sets a target of nearly $4 trillion in deficit reduction over 10 years, and about two-thirds of it--somewhere close to $2.5 trillion--would come through spending cuts. That's austerity on an unheard-of scale--a reflection of the private sector's decades-long assault on working-class living standards that aims to drive wages down to the level of China.

Obama's proposal does contain some short-term spending initiatives around infrastructure redevelopment and job creation--measures that will mainly be of use at Democratic campaign events since no one in Washington thinks they stand a chance of passing Congress.

But the administration also argues for maintaining strict budget caps in all areas, excluding Social Security, Medicare and defense--the result of which "would bring nondefense discretionary spending down to its lowest level as a share of the economy since" the Eisenhower presidency of the 1950s, according to an analysis by the Economic Policy Institute.

Speaking of defense, the bloated Pentagon budget--which, along with tax cuts for the rich, is chiefly responsible for the ballooning government deficit--will stay just as bloated. For next year, the Obama administration is proposing a reduction of less than 1 percent in core Defense Department spending.

As for Obama's proposals to raise taxes on the rich, the administration's main p.r. message was its support for a so-called "Buffett Rule" to ensure that millionaires pay taxes at a similar rate to middle-income households. The name comes from multibillionaire Warren Buffett, who famously pointed out that he pays taxes at a far lower rate than his secretary. The "Buffett rule" advertised by the administration is supposed to make millionaires pay at least 30 percent of their income in taxes.

But as the New York Times reported, if you look for an actual Buffett Rule "among the myriad tax changes the White House detailed in the 2013 budget proposal...you will not find it."

After the release of the budget--and a flurry of speeches by Obama in which he claimed his proposal would make the rich pay their "fair share"--the White House clarified that the Buffett Rule was merely a "guideline," not an actual proposal to change in the tax code.

Any attempt to implement the Buffett Rule, according to administration officials, will come as part of a broader overhaul of the tax code--which will contain further tax "reforms" designed to entice business support, says the White House. For example, the administration this week proposed decreasing the corporate tax rate to 28 percent--despite the fact that business' contribution of overall tax revenues has dropped to a new low.

As for what's actually in the budget, the chief component of the Obama proposals on taxes is the elimination of Bush-era income tax breaks for the super-rich. This would raise the marginal tax rate paid by top-income households from the current 35 percent to the 39.6 percent rate of the Clinton years--when, by the way, the U.S. economy enjoyed the longest sustained expansion in its history.

If those numbers sound familiar, it's probably because the Democrats talked about them a lot during the last several election campaigns. Barack Obama vowed in 2008 that he would let the Bush tax cuts for the very richest households expire when they ran out in at the end of 2010.

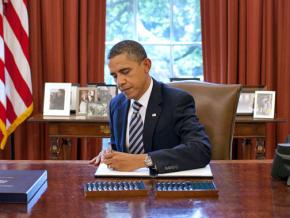

But once he moved into the Oval Office--with Democrats holding the biggest majorities in a generation in both houses of Congress--Obama did nothing for the better part of two years. With the expiration approaching at the end of 2010, Democrats caved on forcing a vote in Congress before the November election, which would have put Republican lawmakers on record supporting tax cuts for the rich. Instead, the issue was decided in a lame-duck session in November and December, where the Obama administration capitulated entirely and agreed to extend the Bush tax cuts for everyone, including the super-rich.

So keep that in mind next time you hear Obama wants to tax the rich. If he actually did, he could have relied on majority opinion and waged a fight to let the Bush tax cuts expire in 2010. Instead, he "compromised"--and gave the Republicans exactly what they were asking for all along.

OBAMA'S BUDGET is a product of a Washington system where the politics of austerity have an iron grip on the leaders of both major parties. The "liberal" Obama is putting forward proposals for spending cuts--including in cherished programs like Social Security--that budget-cutting Republican maniacs like Ronald Reagan or Bush Sr. and Jr. once only dreamed about.

That's a far cry from when Obama took office three years ago, only a few months after the near-meltdown on Wall Street shook the world financial system and the recession was starting to hit hard. Back then, large parts of the business and political establishment were united around the need for increased government spending to stop the Great Recession from becoming a Great Depression.

In the first months of his presidency, Obama pushed through a $787 billion stimulus measure--roughly the same size as all the 1930s New Deal programs, though it was weighted to corporate tax breaks. Republicans opposed the legislation, but didn't try to block it, as they have virtually every Obama initiative since.

But even as he pushed for this one stimulus measure, Obama and his team of Wall Street-schooled economic advisers made it clear that the administration would place a high priority on deficit reduction through large cuts in government spending.

Rather than seek additional stimulus measures after the economy failed to produce jobs, Obama instead imposed a pay freeze on nonmilitary federal workers. He formed a presidential task force with the mission of making deep cuts in Social Security. And during last summer's debate over raising the debt ceiling, Obama dueled with Republicans to propose the deepest cutbacks, even vowing to drive through Social Security benefit reductions if the GOP agreed to modest tax increases on the rich.

The same political dynamic has repeated itself on one issue after another: Obama and the Democrats present a compromised proposal designed to "meet the Republicans in the middle." The Republicans refuse to consider it and make even more extreme demands. The Democrats compromise on their compromise, and retreat from their retreat. And so on, until the final "compromise" ends up being what the Republicans proposed in the first place.

Why has this happened? Is the problem that Obama and the Democrats are just spineless?

Spineless, they may be--but the more important reason is the role that the Democrats play in the U.S. two-party system. Aside from the occasional campaign-trail comment about Wall Street, the Republicans are open and proud advocates of the interests of big business. But the role of the Democrats is to pose as representatives of working people against corporate power--while acting in office as defenders of the same business interests as the Republcians.

The Democrats' endless compromises are the result of having to face two ways--to say one thing to win votes at election time, and to do another once in office.

As Jeffrey Sachs wrote in his analysis of the Obama budget, this means working people don't have any party defending their interests in Washington:

Even as Democrats today praise Mr. Obama and Republicans castigate him for his headline proposals to tax the rich, the budget is actually more grim news for America¹s poor and working class. The poorer half of the population does not interest the Washington status quo. A third political party, occupying the vast unattended terrain of the true center and left, will probably be needed to break the stranglehold of big money on American politics and society.

While a genuine third-party challenge from the left is unlikely to develop in the coming eight months before November, there is another force that can "break the stranglehold"--the revived working-class movement that captured the attention and imaginations of millions last year, from the uprising in Wisconsin last winter to the rise of the Occupy movement in the fall.

The struggles of that movement--large and small, in workplaces, communities or campuses--can provide an alternative the politics of austerity and social conservatism that dominate in Washington. Anyone who wants to see that alternative grow and flourish needs to devote their energies to mobilizing those struggles throughout this year, not supporting Barack Obama and the Democrats in Election 2012.