Social justice changemakers

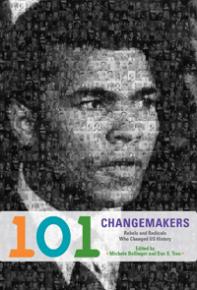

A new book written for middle-school students--101 Changemakers: Rebels and Radicals Who Changed U.S. History, edited by and --offers a "peoples' history" of some of the individuals who shaped this country. In the place of founding fathers, presidents and titans of industry, 101 Changemakers includes profiles of people who fought courageously for social justice. Every "changemaker" is remembered with a short biography and timeline of their life, plus suggestions for more to do and questions to consider.

SocialistWorker.org is publishing excerpts from 101 Changemakers all week. Today's focus is on struggles against oppression and for social justice.

Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon

(1921-2008; 1924-)

In an era when it was illegal for a woman to love another woman, Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon lived openly as lesbians.

They helped found the first national lesbian organization, the Daughters of Bilitis (DOB), and its magazine, The Ladder. Del grew up in San Francisco. Phyllis grew up in Oklahoma. They both went to college in Berkeley, California, but they did not meet until 1950, when they worked for the same magazine in Seattle.

Del and Phyllis became lovers in 1952, a time when men and women who were physically attracted to people of the same gender were considered mentally ill. Lesbians and gays were often fired from jobs and shunned by their families. It was difficult for lesbians to meet each other. Even bars for lesbians were against the law and police sometimes arrested women who went to them.

In 1955, Del and Phyllis, along with six other lesbians, organized the DOB in San Francisco. The group became a social space for lesbians to meet. It also worked to challenge society's discrimination and the laws that criminalized their love.

Phyllis was the first editor of the DOB's literary magazine, The Ladder, which published fiction, poetry, and research that showed that women who love women are perfectly normal and could be happy if society's laws would change.

Phyllis earned a doctoral degree in human sexuality so that she could lecture and write to help mobilize a movement to change the laws. Del also spoke publicly and wrote widely to explore and speak out against the false idea that women are weaker and less intelligent than men. And Del organized, wrote, and spoke out to win justice for women who were physically abused by their husbands and boyfriends.

During the 1960s the African American civil rights movement influenced Del and Phyllis. They believed fighting for the freedom to love a person of the same gender was also a civil rights struggle, which was a radical idea at that time. Despite the racism that dominated in the fifties and early sixties, the DOB was open to all women. It also did not bar people for their political beliefs. One of the founding members was a Latina, another was a Filipina, and the group's president from 1963 to 1966 was a black woman, Cleo Bonner.

SocialistWorker.org is running excerpts from 101 Changemakers: Rebels and Radicals Who Changed U.S. HistoryFrom 101 Changemakers

In part because of their efforts to fight for equality, laws and ideas in society about lesbians changed. After fifty-five years together as a couple, Del and Phyllis were among the first lesbians to legally marry on June 16, 2008, two months before Del passed away.

The movements they helped launch have made it possible for millions of lesbian women in the United States to be who they are openly and be accepted by their families, friends, and coworkers.

Del and Phyllis wrote two books together: Lesbian/Woman (1972) and Lesbian Love and Liberation (1973). Many of their ideas about gender and sexuality are useful to a new generation who are continuing the struggles they helped start.

-- Sherry Wolf

Timeline:

1921: May 5, Del born Dorothy Louise Taliaferro in San Francisco, California

1924: November 10, Phyllis born in Tulsa, Oklahoma

1955: Four female couples, including Del and Phyllis, form the Daughters of Bilitis, the first national lesbian organization in the United States

1956: Phyllis becomes the first editor of the new organization's newsletter, The Ladder. Until 1957, she uses a false name, Ann Ferguson, to protect her privacy

1965: Members of the Daughters of Bilitis join gay men and picket outside the White House for the first time to demand equal rights for lesbians and gays

1972: Del and Phyllis co-write the award-winning book Lesbian/Woman

1973: they write Lesbian Love and Liberation

2008: Married on June 16 in the first same-sex wedding ever to take place in San Francisco; August 27, Del dies at age 87 with Phyllis by her side

Barbara Young

(1947-)

Barbara Young is one of the key organizers of the National Domestic Workers Alliance (NDWA). She is a former care provider who mobilizes domestic workers to improve their conditions.

There are about 2.5 million domestic workers in the United States. Even though their work is enormously valuable, they often face long hours for low pay. Many have no health insurance through their employers and are often denied paid time off when they are sick. Immigrant women, some undocumented, make up most of the workforce. They sometimes experience racism as well as physical and other forms of abuse. Some are even modern-day slaves, illegally sold and forced to work in terrible conditions. These are some of the issues Barbara tries to address. She speaks to activists, trade unionists, government officials, and many others to get her message across: domestic workers deserve to be treated with fairness, respect, and dignity.

Barbara grew up in a small town on the tropical island of Barbados in the Caribbean. Her mother was a homemaker and her father worked on a sugarcane plantation. He was very active in a union that defended the rights of his fellow workers. When Barbara finished school she moved to St. James, a bigger town on the island. There she worked as a bus conductor and was an activist in her union. "I'm very friendly and outgoing," she said. "And I just want to see people treated in a fair way." She worked for twenty years as a conductor until the government cut hundreds of jobs. The conductors were replaced by fare boxes and Barbara could not find well-paying work.

She decided to join her daughter in New York City in 1993. When Barbara first arrived she worked as a caregiver for an elderly person in Queens. Later she took a job as a live-in childcare provider, or nanny, and looked after the young children of working couples. She worked as a nanny for seventeen years. Barbara's work in this country has always been caring work. And it is "work that makes all other work possible." But she has had to endure a lot over the years. She recalls how one employer paid her the bare minimum for her daily nannying work and then expected her to sleep in the room with and feed an infant overnight, all for no extra pay. She explains: "Because you work in the home, people don't see you as an employee. It's seen as women's work, not proper work."

By 2001 she was talking to other care providers about banding together to better conditions for domestics. Domestic workers, like farmworkers, are specifically excluded from the National Labor Relations Act of the 1930s, the law that allows workers to form unions. Workers in private homes regularly operate in the shadows. Their pay and conditions are set by their employers without proper regulation. Barbara and others joined forces with Domestic Workers United to win basic labor rights for nannies, housekeepers, and caregivers.

In 2010 workers won a domestic worker bill of rights in New York that says they should have basic rights and protections including a forty-hour week, paid days off, overtime pay, and the right to organize as a group.

Barbara knows more rights like these for domestics would make a huge difference. "It recognizes domestic work as real work."

-- Dao X. Tran

Timeline:

1947: Born Barbara Scantlebury in St. Peter, Barbados

1965-85: Works as Barbados Transport Board conductor; represents Transport Board workers on the Barbados Workers' Union's executive council

1993: Emigrates to New York; works as a caregiver in Queens

1993-2010: Works as a nanny in Long Island and New York City

2001: Begins agitating for better conditions for domestics and joins forces with Domestic Workers United (DWU)

2003: Successful campaign for New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg to sign a bill protecting domestic workers working through an agency

2004: Joins DWU's steering committee; helps expand DWU's membership and deepen its impact; works to build a global domestic workers' movement 2010 Domestic Workers' Bill of Rights in New York passes; Barbara takes job organizing full time for NDWA

2011: NDWA launches Caring Across Generations, a national campaign to address the working conditions of people providing direct care to our nation's elderly and people with disabilities